Swirls of creamy pearl and lavender, sunset streaks across sky blue, and the pulsing shades of floral bloom flow through the Facebook page of Mary Rose Sancelan. The pastel hues carry psalms of gratitude and faith, and a few cries for deliverance.

A deep faith in God and her brethren on earth rooted Dr. Mary Rose Sancelan to Guihulngan, a city hemmed in by mountains and a narrow strait on the northern flank of Negros island in the central Philippines.

“The Lord will guard us as a shepherd guards His flock!” stands out against a soft background of pink and yellow — shy lemon and salmon, bold coral and the warmth of sunlight as it starts to welcome dusk.

“What heals us in this crisis is the humanity in each person. We shall overcome.”

Both messages popped up on July 24 this year as Salcelan, who sometimes served as lone state doctor to 100,000 residents of a poor city, raced to contain the first local cases of COVID-19.

As city health officer, Sancelan was head of the local Inter-Agency Task Force on Emerging Infectious Diseases (IATF), which manages the government’s response to the pandemic.

Days earlier, her words were more forceful: “You saved my life O Lord, I shall not die!” And, “from the Heaven, the LORD looks down on the earth!!!” The second passage popped from shades of pink and purple and blue, all mixed in the shapes of desert dunes.

The pandemic severely tested but did not threaten Sancelan’s faith. Nor did another threat that cast a big shadow over the doctor’s life.

Sancelan defeated or, at least, temporarily pushed back COVID-19 after months of perseverance.

The second threat — which vowed death to communists and inexplicably tagged a doctor swamped with public duties as spokesman for the regional guerrilla front of Asia’s longest-running agency — snuffed out the life of a people’s servant and that of her husband.

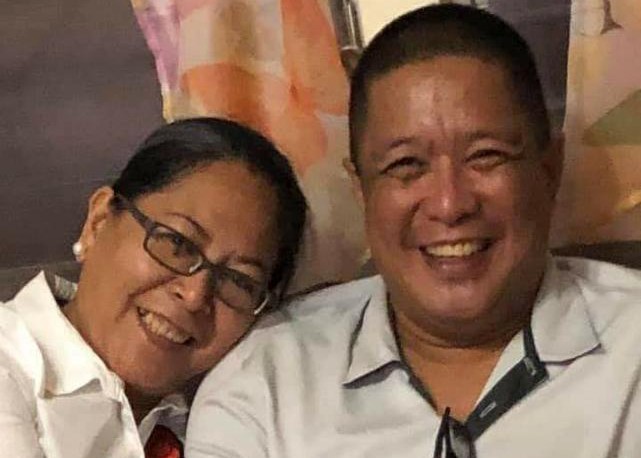

Two men riding shotgun killed the medical professional and husband, Edwin, also a government worker, shortly before they reached their home at the end of work day on December 15.

The attack came a few hours after the release of the International Criminal Court’s Office of the Prosecutor of a document that touched, among other cases worldwide, extra-judicial killings linked to President Rodrigo Duterte’s drug war.

The report found “reasonable basis” to believe Duterte’s campaign may have led to crimes against humanity.

The couple’s blood soaked the earth of Guihulngan as newscasts began reporting the government’s jeers in response to the ICC preliminary findings.

A waste of time, said the office of Duterte.

You can’t touch us, said aides of the man who took out the country from the ICC to evade accountability for killings that have long surpassed the toll of the two-decade Marcos dictatorship.

“I thought it was a welcome news among us peace-loving Filipinos,” said Bishop Gerardo Alminaza, whose San Carlos diocese covers Guihulngan.

“Suddenly, a few hours after, assassins murdered Dr. Mary Rose Sancelan and her husband Edwin. It was brutal, marked by a desire to end the pro-people service of Dr. Sacelan to her constituents.”

Shadow of death

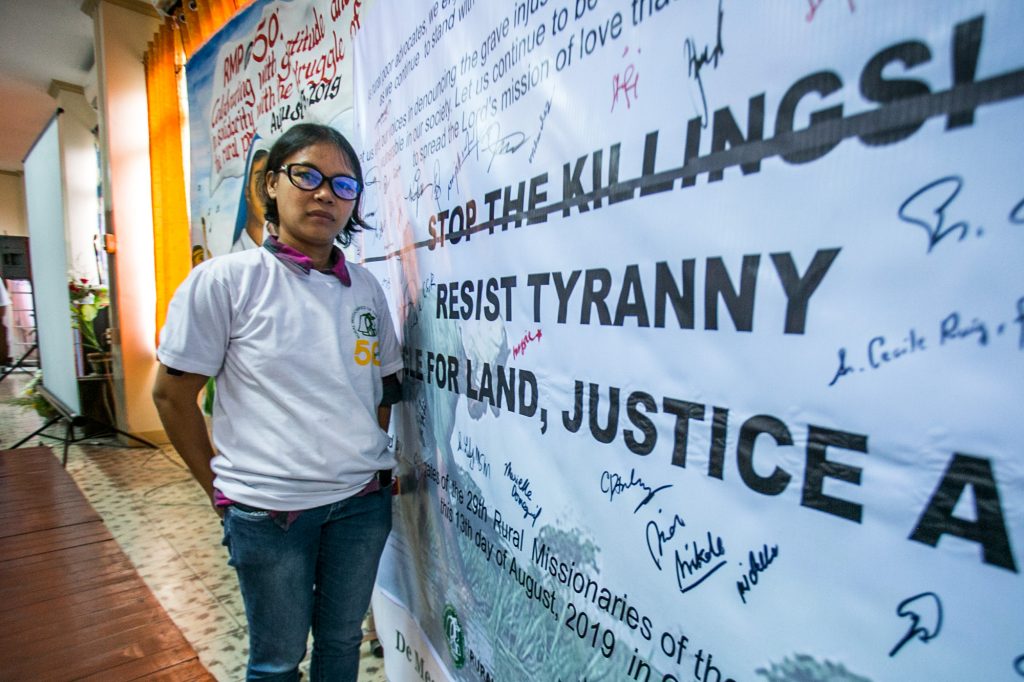

Bishop Alminaza brought Sancelan’s dilemma public in September last year.

At a forum hosted by the Philippine Ecumenical Peace Platform, the bishop warned that red-tagging could brutalize a circle wider than its actual target.

“A medical doctor in the city health office found her name in the list. Fear for her life prevented her to provide health services to 33 barangays (villages) in that city,” said the bishop.

Sancelan then spoke on video.

“I am the only doctor servicing Guihulngan. My workload is very heavy, mostly not just consultations because I also have administrative tasks,” said Sancelan, who would later get badly-needed help with a second city health officer.

The doctor’s calm mien, her soft, liltling tone and accent, made her next words a sudden cold slap.

“I was accused of being JB Regalado, a commander or local head of the CPP-NPA,” the doctor said. Regalado is the nom de guerre of the spokesman of the Leonardo Panaligan Command, which oversees the Central Visayas operations of the New People’s Army.

Sancelan had more than enough reason to worry in September 2019.

Bishop Alminaza’s diocese had already witnessed a bloodbath among sugar workers, rights defenders, church workers, retired government professionals, even lawyers.

Some would die in police-military raids. Officers trotted out the usual “nanlaban” (they fought back) excuse so familiar in the thousands of deaths linked to Duterte’s “war on drugs.” The victims’ kin would later testify hearing them beg for their lives, insisting they were executed.

On the same list that featured Sancelan were the names of Anthony Trinidad and Heidie Malalay Flores. Trinidad, a lawyer, and Flores, a teacher, had been slain after the red-tagging posters spread across the poblacion, or city center, and rural villages.

A month before Bishop Alminaza brought Salcelan’s case to Manila’s attention, the city police chief spoke before a Senate inquiry into the spate of killings of civilians, believed to be state reprisals for a rebel ambush that killed four intelligence agents.

The police officer said five of 15 names on the hitlist of an anti-communist vigilante group called Kawsa Guihulnganon Batok Kumunista (KAGUBAK) had been killed.

Trinidad, number 14 on the list, was felled in a daylight ambush in the city center. Flores was 11th on the list.

Proxy killers

Rights defenders said you could track the killings with the appearance of the red-tagging posters.

The slurs thrown at Salcelan seemed farcical.

As a daughter of another woman government doctor, I knew their work hours went beyond nine to five, beyond a five-day workweek. The desperate poor would knock on their homes at odd hours, bringing gasping children, adults felled by sudden weakness, people wracked with coughs, sometimes a neighbor wounded in a drunken brawl.

Weekends often meant a trek to isolated rural hamlets where people could leave an entire life without seeing a medical professional. Sancelan’s Facebook page showed many such missions, with men and women, the old and the young lining up for treatment.

In many photos, she was the lone doctor. In some, she had volunteers to help. Even without COVID-19, she could not have found the time nor the energy, even if she shared the rebel’s views, to be their spokesman.

But Salcelan couldn’t ignore the threat. Her face was pasted on those posters.

And while the allegation seemed ridiculous, gunmen had already killed a doctor in Guihulngan a year earlier.

Like Sancelan, who was a scholar of Franciscan clergy, Dr. Avelex Salinas Amor, a visiting doctor from Canlaon City, had stuck to his youthful dream of being a doctor to the barrios despite offers of work abroad and in the cities. His killers have not been caught.

Then National Police chief Oscar Albayalde, who would later be forced into early retirement by allegations of his links to a cop network that extorted from suspected drug lords, said he had no knowledge of anti-communist vigilante groups.

Other police and military officers shrugged off charges, saying they could not be responsible for the work of vigilantes. It was a refrain familiar to groups monitoring Duterte’s war on drugs, where “vigilante” killings was thrice the number of the 8,000 “official” operational count.

Keeping faith

Pre-COVID, Sancelan bore the burdens of her responsibilities with a trademark wide smile that twinkled even behind heavy black plastic glasses.

“Behind every cloud of sadness is a bigger light of joy!

Thanks Lord for giving me joy in performing my favorite job and that’s sewing people up!

Lacerated wounds on the base of the left index finger and parietal area of the head!”

From any other person, it would sound a bit off, stopping short of gallows humor. But to people who knew “Doc” it represented the droll humor of a hardscrabble community dependent on the corn and coconuts of a poor soil and waters that barely offered enough catch for daily sustenance.

For a few weeks, Sancelan withdrew to deal with the trauma of being red tagged. Kin and friends urged her to flee to safer ground.

But the doctor battled through fear and decided to stay put as a people’s servant.

Aside from her COVID-19 duties, she was also nutrition action officer. That is service with the weight of half of Mount Canlaon, the sacred volcano that straddles the spine of Negros island. The oriental side, which Guihulngan belongs to, has a poverty incidence of 45 percent, double that of the 21.6 percent national average.

Following the murders, the COVID-19 task force issued a statement lamenting “the loss of courageous and dedicated frontliner who was instrumental in placing under control the previous spike of COVID-19 cases in the city last November.”

Sancelan had battled back a new spike of COVID-19 cases in October, which coincided with rising infection rates across the province of Negros Oriental.

“We are confused and shocked (at) of this painful fate befalling our fellow public servants,” said the task force statement, which warned of a “void” in the service.

Guihulngan needed Sancelan like a person needs air.

The task force did not exaggerate the challenges Sancelan faced as medical professional.

There is only one public doctor per 31,000 Filipinos and the national health scales have always been lopsided, with most professionals and resources serving the national capital. Two-thirds of of private and public hospital beds are in the island of Luzon, which includes the National Capital Region.

The World Health Organization cites “regional and socioeconomic disparities in the availability and accessibility of resources.” There are 23 hospital beds for 10,000 people in the capital while the rest of Luzon, Visayas and Mindanao have only 8.2, 7.8 and 8.3 beds, respectively.

The Council for Health and Development, a national organization of community based health programs in the Philippines, expressed rage that “impunity knows no bound even at a time when the whole nation is gripped by the pandemic.”

The killers deprived the people of Guihulngan much needed health services especially in this most difficult time, the group warned.

Serving god, serving the people

Sancelan, Bishop Alminaza said, was a Christian who lived Jesus Christ’s most important message: to love your neighbor as you love God.

“This is too much. This is totally unacceptable to allow it to happen to public servants who were working so hard to serve the public interest especially during this pandemic,” said the bishop soon after news of the murders broke out.

“Dr. Sancelan was branded, vilified, red-tagged, and now, executed, by the ruthless pawns of the enablers of ‘systematic killings’ in this country,” added Bishop Alminaza.

“Her only crime, much like the soon-to-be born-infant Jesus in a manger, was her unselfish service to the poor people of Guihulngan—both as a ‘barrio doctor’ and as ‘defender of the poor,’” he added.

Military officers, a year after the Senate hearing that featured the Guihulngan killings, have taken the place of anonymous groups in leading the attacks against perceived enemies of the state.

They have over the last two years named clergy and religious workers, indigenous leaders, legislators, medical workers, journalists, leaders of mass organizations, human rights workers, youth activists, feminists, even global aid charities and UN experts.

There has been no rhyme nor reason, and even less evidence. The military and Duterte reassured Filipinos: they are communists and terrorists because we say they are.

Over four years, some 20,000 have fallen in a drug war that operated on exactly that same worldview. Duterte has now said he will carve a bloody swathe through the body politic, with blanket screaming “the crime of one is the crime of all” covering all dissenters.

In the face of the rising threat to the most basic of human rights, Bishop Alminaza, himself a frequent target of red-tagging, reminded government officials and the faithful in Asia’s largest Catholic majority: “It is a grave omission to remain silent and passive and allow perpetrators to get away.”

“Join me in prayer in the face of unstoppable murders in our diocese. Join me in hope that these killings will soon end. But join me, too, in condemning, in the strongest possible terms, the senseless murder of helpless civilians and dedicated servants of government.”