“Time pays no attention to the borders we erect to fool ourselves into believing we control it.”

While preparing for this piece, I was reminded of these words by Uruguayan journalist Eduardo Galeano. Speaking of the frontiers of the new millennium which the world both celebrates and fears, he placed much of our presumptions of the future in its proper perspective:

“If we can’t guess what’s coming, at least we have the right to imagine what future we want,” he further said.

Disaster waiting to happen

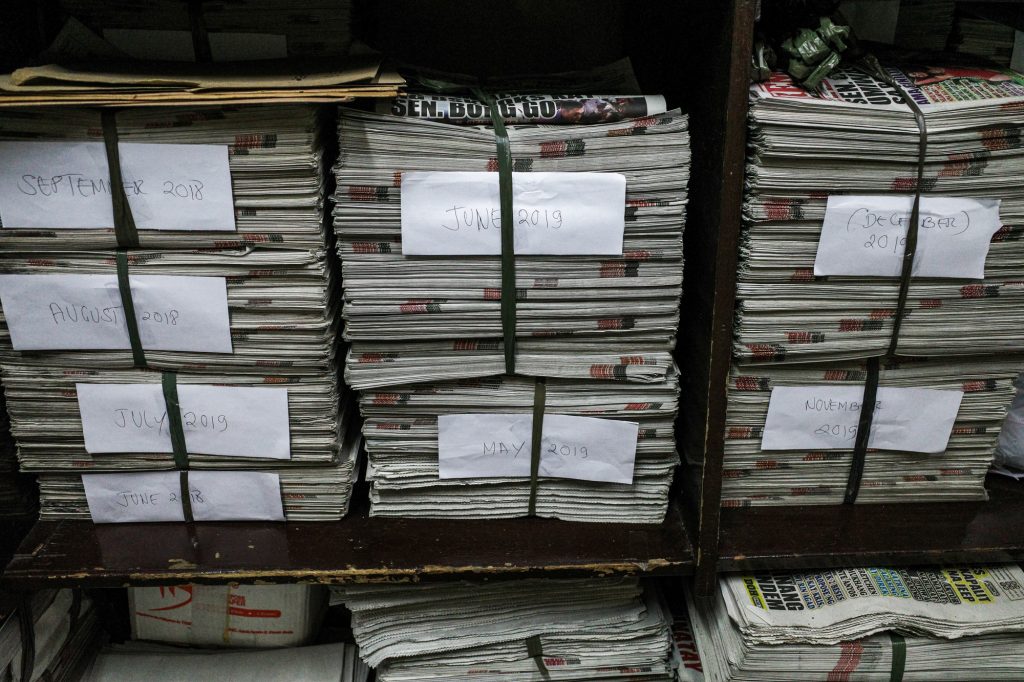

It was on the morning of the last day of June when, without warning, I received my retrenchment papers from the political and literary magazine where I sat as editor-in-chief for the past 11 years.

I didn’t expect my retrenchment to come bearing the silence of the mortuary. I simply wasn’t previously informed. Nearly a month later, in the same token, my wife, who sat for the last eight years as lifestyle editor for a tabloid, also received her retrenchment letter. The publications have since migrated online, or so I was told.

As early as March, the start of the lockdown, I knew it was a catastrophe waiting to happen. Print media in the Philippines had been under tremendous pressure to operate given the lack of advertising for many years prior to Covid-19. Much of the staff of nationally-circulated newspapers had to settle for survival wages, if wages come at all.

The arrival of the pandemic shook the very foundations of what had been brittle from the start. Harassment, intimidation from government and the recent shutdown of ABS-CBN Network forced the media into a defensive, fighting a battle on three fronts: a government adverse to criticism, a raging pandemic, and media outfits forced financially to its knees.

The bigger picture

The Philippine media is but one of numerous organizations around the world which have had the misfortune of being forced into a corner with the coming of Covid-19.

RFI, part of a group of international French broadcasting stations headed by France Médias Monde, reported that “Major dailies in Brazil and Mexico have already switched to online-only or dropped some days’ editions, while in the Philippines 10 of the 70 newspapers in the PPI association have shuttered.” The Philippine Press Institute or PPI is one of the oldest press organizations in the country.

The report further said, “The archipelago nation’s small local newspapers were hardest hit during lockdown as street sales tumbled […] Far from affecting only journalists, the disappearance of print papers deals out pain all up the production chain, taking in printers, paper makers and delivery people.”

In the United States, the latest tally of closures of community newspapers since July have reached more than 50, according to a Poynter report.

“Now, small newsrooms around the country, often more than 100 years old, often the only news source in those places, are closing under the weight of the coronavirus. Some report they’re merging with nearby publications. But that ‘merger’ means the end of news dedicated to those communities, the evaporation of institutional knowledge and the loss of local jobs.”

The Guardian, a reader-funded news website reporting on what it called “extinction level” crisis hitting newspapers in the U.S., painted an ironic picture of the situation: “For a journalism industry already barely scraping by, the impact was almost immediate […] The Plain Dealer, a daily newspaper in Cleveland, Ohio, laid off 22 newsroom staff – including its health reporter.”

Migrating online

The spread of the Covid-19 forced numerous press organizations to either close, merge, or consider online presence. In the UK alone, more than 2,000 newspapers either folded or merged due to the pandemic. BuzzFeed, a popular news site, is reportedly closing its UK and Australian operations.

Upon closer observation, it is largely ironic that news consumption has surged during the pandemic even as newspapers begin to fold, but in ways no one in the media industry seemed to have foreseen during pre-Covid-19 days. Studies have shown that in 2018 and 2019, news consumption via online sources have dipped significantly after years of continuous growth due, perhaps, to the onslaught of “fake” news.

The Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020 says that its global findings in 40 countries point to a current surge in news consumption via online sources, with 14% turning to television news. Facebook leads the pack of online applications at 35%, and YouTube and What’sApp at 30% and 23%, respectively.

This surge, fueled by the spread of Covid-19, seem to converge only within very few countries: 20% in the U.S., 42% in Norway, and 14% in the Netherlands. News brands taking the lion’s share of the market include The New York Times, The Washington Post, The Sunday Times, The Telegraph, to name a few.

The study says that the main problem with migrating online is mainly focused on trust and the integrity of news sources. Across the world, about 56% of news consumers are “concerned about what is real and what is fake online when it comes to news”.

About 40% blame politicians for the surge of fraudulent information. Roughly 14% believe it’s the fault of activists, with 13% blaming journalists. As for the distribution of fake news, Facebook takes the cake at 28%.

Press Freedom: Under siege?

With failing financial health topping the threat of the new coronavirus and a government hostile to criticism, the study asks the question, “Will financial frailty affect the independence of new media? How can publishers weather the storm?”

It is indeed a tragedy that Covid-19 has left much of the media industry unable to cope with the financial meltdown. Let’s not even go to where field work or investigations into the shenanigans of government had been rendered well-nigh impossible due to the threat of infection.

Filipinos fear that laws like the Anti-Terrorism Act and the Anti-Cybercrime Act have been weaponized to go against government critics.

No sooner than the tally of active infections breached the 100,000th mark, government insisted on the reinstatement of the death penalty, with the newly-installed Armed Forces chief proposing to use the Anti-Terrorism Bill to regulate social media.

With a 61% drop in crime rate for the duration of the lockdown, the police busied themselves with red-baiting government critics using Facebook.

Virus at the door, wolves at the gates

The problem is as damaging as it is complex. There are no easy answers. The virus at the door doesn’t make the wolves at the gates any less hostile to press freedom as they are to journalists themselves. Journalists have had the distinction of being called by many names, not all of them flattering.

It is nevertheless imperative that journalists take the blows just as frequently as they can dish it out. The feats that had won recognition for individual journalists must now equal the courage which would lead the industry to accomplish greater things in solidarity with one another. The time has come for us to unite.

The future, I still believe, is rife with possibilities, if we are brave enough to imagine and create one for ourselves. And what better way to do this than to adapt to the changing landscape of the times.

However, there’s no reason to drop tradition altogether. Media independence is crucial to public trust. It is thus every journalist’s moral obligation to stand the test of these challenges by sticking to what makes us real journalists in the first place —

The truth.

Joel Pablo Salud is an editor, journalist and the author of several books of fiction and political nonfiction. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official editorial position of LiCAS.news.