By MICHELLE MABINGAY and NEIL AMBION, Bulatlat.com

Sugarcane workers in a vast sugarcane field in Batangas province pay no mind to the cuts on their arms and soles as they wade through thorny crops with their calves.

Last November, they harvested sugarcane in Batangas. Alfred Manalo and Lloyd Descallar, workers of Central Azucarera Don Pedro, Inc. (CADPI), were not able to work. They’ve been in military custody for the last nine months.

On the afternoon of March 26, 2023, the 59th Infantry Battalion ng Philippine Army (59th BPA) abducted them outside the Medical Center Western Batangas in Balayan town.

Angelito Balistoso, a pipe worker who happened to be nearby, was also abducted. The military says all three are leaders of the New People’s Army.

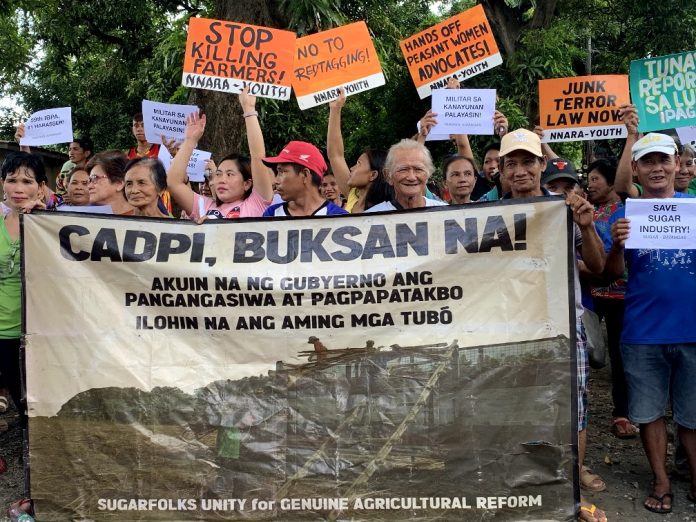

Alfred and Lloyd were in Balayan as volunteers of the Sugarfolks Unity for Genuine Agricultural Reform (SUGAR), an association of farm workers in Batangas sugarcane plantations.

They were holding consultations with other workers affected by the sudden closure of the sugar mill.

CADPI is owned by Roxas Holdings Inc. (RHI), the biggest integrated sugar business in the country. It owns 10,980 hectares of sugarcane fields across the towns of Nasugbu, Lian, Tuy, and Calatagan in Batangas. It can process 13,000 metric tons (MT) of sugar every day.

The RHI gave no notice to 125 regular sugar mill workers, 12,000 farm workers, 5,000 small planters (working in sugar fields less than 5 hectares), and over 1,000 drivers and porters affected by CADPI’s closure.

In a letter, dated December 15, 2022, to the Sugar Regulatory Administration (SRA), RHI president and chief executive officer Celso Dimacucut said he would close the CADPI’s boiler, steamer, and milling department.

He claimed that the quality and sugarcane supply was declining, adding that the profits were not enough to sustain the operations.

But for Sugar, the “profit losses” and decrease in production in the last few years were brought about by land use conversion, lack of state support, and widespread importation.

“Alfred Manalo and Lloyd Descallar shouldn’t be the ones suffering [because of the sugar mill’s closure],” said Christian Bearo, the group’s spokesperson.

Bitterness of sugarcane workers

A year after CADPI’s closure, Bearo said that around 400,000 MT of sugarcane rotted away, worth P1.8 billion (USD 17.9 million) in 2023. Small planters are the most affected by the losses.

In May, Universal Robina Corp. (URC) purchased what was left of the sugar mill’s capital in Batangas, including the milling machinery. It can only process 8,000 MT now.

The crops of many planters weren’t deemed a priority to be processed by URC and were left unused. The few planters who did manage to sell their sugarcane to URC say they were given substandard rates.

“Because URC monopolizes the buying of sugarcane in Batangas, they cheated the planters and their sugar content. So the planters got a small share, a 60-40 exchange for planters and millers, smaller compared to that in Negros which is 70-30,” said John Milton “Ka Butch” Lozande, secretary general of National Federation of Sugar Workers (NFSW).

Bankruptcy caused many planters to stop production, with farm workers and drivers who relied on the industry heavily affected.

Ricky Biamonte left his home in Quezon province in the hopes of finding work in the Batangas sugarcane plantations. He has cut sugarcane for 20 years. When the sugar mill closed, his family could hardly afford to eat.

“We used to earn P1,500 (USD 26.86) [each week], now we can’t make this much anymore. Realistically, we make P300 (USD 5.37) a week now,” he said.

Nowadays, in a week, they’re able to cut sugarcane between two to three times. He has also been forced to find side jobs with measly pay.

“When our earnings were good, my kids could go straight to school. Now, I can’t give them any allowance so they’ve stopped school,” Ricky said.

During this harvest season, the farm workers have no idea if they’ll earn something, or just enough to pay off some debt.

“The Marcos [Jr.] administration did nothing to mitigate this. Through the efforts of the Makabayan bloc, House Speaker Martin Romualdez was convinced to provide P10,000 (USD 179) aid to the workers, but the full amount hasn’t been given yet,” said Lozande.

Instead of aid, the state sent battalions of its soldiers to the CADPI workers. Since then, human rights violations have been seen throughout the year.

Several times in August, the 59th IBPA barged into houses in Putol village in Tuy. They harassed and threatened the residents. They also disrupted a village meeting for Romualdez’s promised aid.

On November 20, Karla Mae Monge, a former student at the University of the Philippines Los Baños researching land use conversion, was kidnapped on CADPI land.

Ricky shared that soldiers have repeatedly threatened him himself.

“They neglected us, can they blame us if we assert our rights to aid and compensation and demand that the government reopen and manage the CADPI?” said SUGAR in a statement.

Industry sabotage

Despite not buying sugarcane from local producers, RHI is still able to sell sugar. For every sack, the company imports raw sugar at P450 (USD 8). They process and sell it to the local market for up to P3,250 (USD 58.20) per sack.

According to SUGAR, this is an economic sabotage by the RHI because it sacrificed the local industry to cut down the cost of production and for “profiteering.”

Aside from sugarcane workers in Batangas, many sugarcane plantations in the provinces of Cavite, Laguna, and Quezon rely on CADPI to process their harvest.

According to a report from the United States Department of Agriculture, the harvest season in the Philippines this year will yield 1.322 million MT of sugar stocks, lower than the 1.465 million MT from 2022. Sugar production in the country has been stagnant for two years.

Rising prices come with a dwindling supply. The government imported sugar to fill the demand. Last May, Department of Agriculture (DA) Senior Undersecretary Domingo Panganiban promised to lower the price of sugar to P80 per kilogram because of additional imports.

According to SRA data last November, 68 percent or 142,800 MT of sugar in the market were imported. But this December, sugar costs P100.39 per kilogram according to NFSW.

“It is clear that [lower price] won’t happen. SRA and DA only want to maintain the super profits of big landlords and millers, who do not just produce, but are also permitted to import,” said Lozande.

He added that Ferdinand Marcos Jr.’s government is also setting up cronies in the sugar industry.

Because of increasing imports, the millgate price or the price from local producers decreased to P2,500 (USD 44.77) per sack of sugar which is a loss for small small producers.

“While the millgate price plummets, retail prices remain high. Clearly, sugarcane farmers and consumers do not benefit from this situation,” said Aurelio Valderrama Jr., president of the Confederation of Sugar Producers Associations, Inc.

Valderrama said that it would help if the government prioritizes the local industry.

Sugar calls for a halt in sugar importation. Instead, CADPI must be reopened and its operation should be directly managed by the government.

For NFSW, the sugar crisis can be solved if landlessness is also addressed.

“Sugarcane production is very costly and the cost continues to increase because of the rise in fertilizer and petroleum prices. Because of this, a lot of farm workers, who became agrarian reform beneficiaries (ARBs), were forced to lease out their lands,” Lozande said.

He said that as long as there is no genuine agrarian reform and production subsidy, including fertilizer, for small sugarcane planters and ARBs, big landlords will have greater control of the sugar industry.

Lozande also said that agricultural lands should not be converted for other purposes.

The harvest season this year has ended in Batangas province. But they pursue their struggle to salvage what is left of their livelihood and the sugar industry—despite militarization and state oppression.

“We will never back down. We will continue fighting for the rights of sugarcane workers and other sectors in the sugar industry,” SUGAR said.

Sugarcane workers shall line up again in the vast sugarcane fields of Batangas in the next harvest season. Hopefully, Alfred and Lloyd can join them in their sweet victory.

This story is supported by the Google News Initiative News Equity Fund.