Vice President Sara Duterte’s declaration of “victory for basic education” was too soon. As Education secretary, she had just re-opened schools last Monday. Her job of reversing the learning crisis has just begun. Since that crisis emerged from two decades of neglect, her six-year term may not be enough to solve it.

It can be said though that Duterte’s triumphalism contrasted the former president, her father’s defeatism. Rody Duterte had closed all schools for two-and-a-half years due to pandemic. “Never mind if this generation produces no doctors and engineers,” he justified his 7,641-island lockdown that also ruined the economy. So much for a political clan that never built a single city high school or college since reigning 30 years ago.

Neighboring countries, isolating only buildings or street blocks, resumed face-to-face classes ahead: Vietnam, May 2020, then July 2021; Singapore, June 2020, then October 2021; Malaysia, June 2020, then February 2022; Thailand, July 2020; and Indonesia, August 2021.

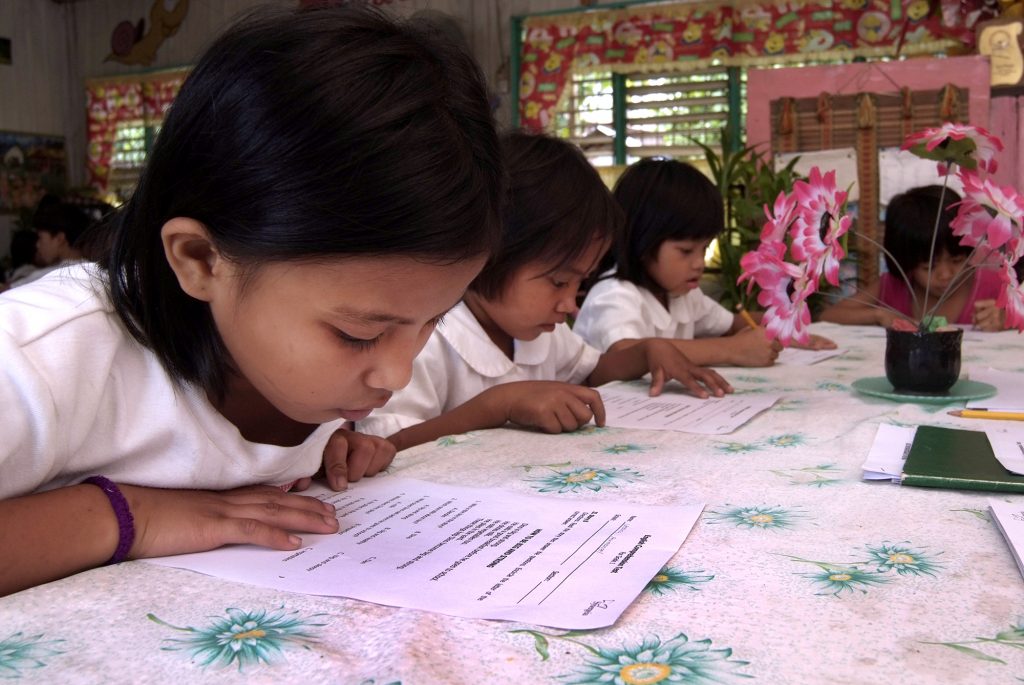

The Philippines resorted to online lessons and printed materials. But poor students lacked gadgets. Wi-Fi was spotty yet costly. Doles from local governments, private firms and NGOs only went so far. Crooked procurers issued teachers PhP2.4 billion substandard laptops. Plus, nothing can replace in-classroom learning where students are focused, and mentors can spot and assist laggards.

Results are predictable. International exams in 2013, 2018, 2019, and 2020 showed that Filipino fourth, fifth and eighth graders were among the poorest worldwide in Math, Science and Reading Comprehension. Primary and secondary graders can only be worse off today. Fifty-three percent of students surveyed in August 2021 were unable to learn the competencies set by the Department of Education. Three in ten were unsure of finishing the school year. Eighty-seven percent suffered bad internet connection. Parents complained that distance learning didn’t work.

With classes back, old problems return. Public schools lack classrooms, laboratories, desks, textbooks, instructional aids, even basic health safety facilities like water faucets. None of those were expanded during the pandemic closure. Teachers are in short supply. Enrollees this year number 28.8 million, 200,000 more than what DepEd anticipated and 1.3 million more than last year’s.

Private schools, traditionally better in facilities and teaching, are in the doldrums. Hundreds have shut down from meager enrollment. One that did on the weekend before school re-opening secretly had sold its campus.

Some that remain operational have resorted to sleaze, pretending to be specialists in Grades 11-12. Bribe of up to PhP5,000 per head is offered to a public school principal to transfer senior high schoolers to the private school. The latter in turn collects from DepEd the PhP18,000-subsidy per student per school year. From just 100 transferees, a corrupt principal can rake in PhP500,000 and the private school PhP1.8 million.

When corruption replaces education as the mission, ignorance spreads. Unqualified teachers are hired, laboratories deteriorate. Graduates march unprepared for Algebra, Biology, Chemistry, Physics, Speech and Language in free college.

Myriad other issues fester. Foremost are teacher training, curriculum revamp and campus upgrades for this age of artificial intelligence and robotics. Congress is reviving the Education Commission for problem solving and comprehensive planning.

Nutrition is linked to learning. If malnourished in its first 1,000 days – from detection of pregnancy to two-and-a-half years old – a child becomes stunted and underweight. With brain half developed, the child is likely to fall behind in learning.

There are residual concerns. Pupils pestered by hair lice, toothache, undiagnosed poor vision and hearing, and hunger cannot focus on lessons. Long city commutes or rural river crossings by foot further bug them.

Duterte must fight in the next six years for a bigger slice of the budget pie. The World Bank prescribes for education four to six percent of any country’s GDP or 15 to 20 percent of public spending. The best in Philippine record was only 3.88 percent of GDP in 2020, and 12.58 percent of the national budget in 2022. Those include funds that went to the Commission on Higher Education.

Jarius Bondoc is an award-winning Filipino journalist and author based in Manila. He writes opinion pieces for The Philippine Star and Pilipino Star Ngayon and hosts a radio program on DWIZ 882 every Saturday. Catch Sapol radio show, Saturdays, 8 to 10 a.m., DWIZ (882-AM).

The views expressed in this article are the opinions of the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial stance of LiCAS.news.