There’s an element of tragedy whenever the president opens his mouth.

In one of his recent press conferences supposedly meant, however belated, to create a calamity response for deluge-stricken Cagayan, Isabela, and the Bicol Region, President Rodrigo Duterte seems to have mistaken the Jesuit-run Ateneo de Manila University for the state-run University of the Philippines.

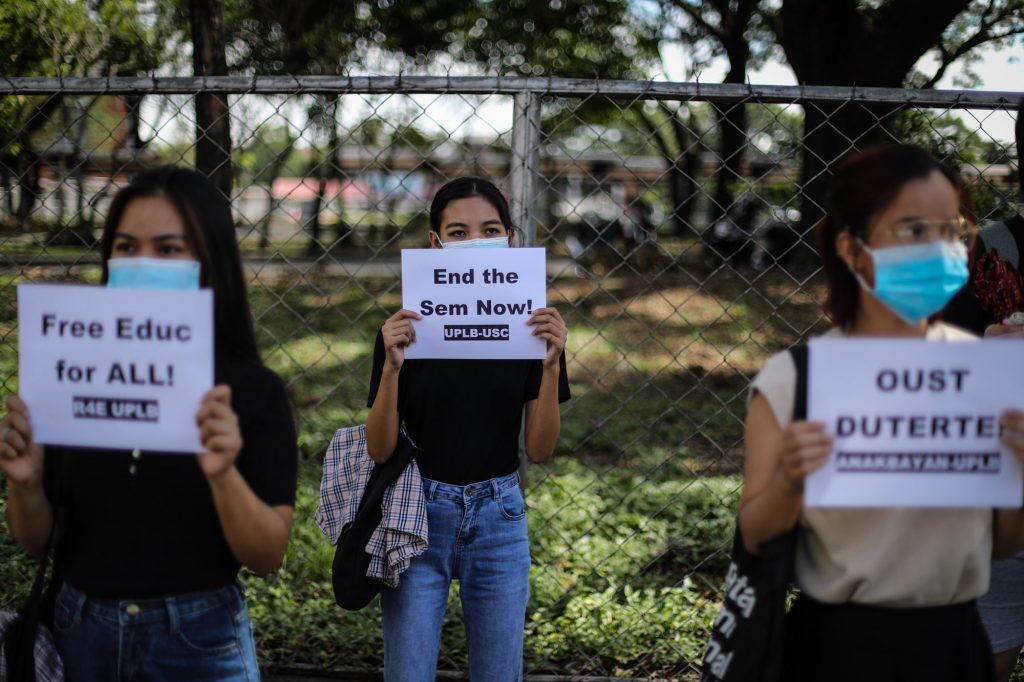

His threat to defund the premier state university came in the heels of a call for an academic strike by 500 students of the Ateneo. For some reason, the President made the gross blunder of dragging UP into the call for a strike.

In a statement released to the Guidon and some mainstream media outlets, the students of Ateneo showed their displeasure at the way government had been handling the crises brought on by several super typhoons and the ongoing pandemic.

“We, the undersigned students of the Ateneo de Manila University, call for a mass student strike against the national government’s criminally neglectful response to the recent Typhoon Ulysses, Typhoon Rolly, Typhoon Quinta and the Covid-19 pandemic as a whole.

“We believe that things cannot continue business as usual. We can no longer stomach the ever-rising number of deaths due to the state’s blatant incompetence. We cannot prioritize our schoolwork when our countrymen are suffering unnecessarily at the hands of those in power. We assert that the Ateneo community must, at the moment, concentrate all efforts into helping the most vulnerable citizens of the Philippines, such as those in Cagayan, Isabela and the Bicol Region.”

The students went on to say that the strike is their way of helping fellow students and professors affected by the crises, particularly those who cannot be expected to complete their modules and studies within the brief span of three to five working days.

“We strike in order to have the chance to be a person for and with others,” the statement said.

According to the Guidon, the official student publication of the Ateneo de Manila, “Until a proper response is made, the signatories have pledged not to submit any academic requirements starting November 18.”

Ateneo bears the distinction, together with the University of Santo Tomas, of having Dr. Jose P. Rizal, the country’s national hero, as its former student. Gen. Antonio Luna, too, joins the list of Ateneo’s illustrious students, which includes artist Juan Luna, Pedro Paterno, Gen. Gregorio del Pilar, Horacio dela Costa, Epifanio de los Santos, and Benigno Aquino Jr. and his son and former president, Noynoy, among others.

Campuses have always been the hotbed of protest action. If history were to be our basis, campuses have made strides in airing their grievances since the 1960s.

Prof. Petronilo Bn. Daroy, in his essay “On the Eve of Dictatorship and Revolution” (Dictatorship and Revolution: Roots of People’s Power, eds. Aurora Javate-de Dios, Petronilo Bn. Daroy, and Lorna Kalaw-Tirol, 1988), said:

“The 60s saw the resurgence of nationalism in the campuses as the students questioned the roots of society’s problems. Inspired by the ideas of Claro M. Recto, the great Filipino nationalist who had been branded by the Americans as a ‘communist’, the students focused on the burning issues of the day, among them the military bases agreements, the parity rights and the Vietnam war. The latter was linked to the sending of a Philcag team in Vietnam which many viewed as involvement in a U.S. war of aggression against the Vietnamese people.”

That inspiration came from a former student of Ateneo—Claro M. Recto.

The decade 1960s to 1970s saw the creation of the largest single student union in the country, called The National Union of Students in the Philippines (NUSP).

According to journalist Recah Trinidad, “NUSP was born out of dissension 13 years ago. The largest union of students in the country was founded by student leaders who seceded from the now-defunct Student Council’s Association of the Philippines (SCAP).”

Ateneo’s Edgar Jopson headed the organization during its heyday.

Duterte has done nothing but scratch the surface, if at all, of the rubrics of crisis management, leaving the people of Cagayan, particularly Linao East, screaming for their lives.

His vain excuse, that he is a night owl, thus caught in the middle of a Cabinet meeting while the province of Cagayan and Isabela drowned in a raging deluge, cannot anymore hold water. Excuses are for losers, and Duterte’s vain attempt to once more fool the people fell now on deaf ears.

These same people, together with a ragtag team of rescuers from the Armed Forces of the Philippines and the Philippine Coast Guard, including chopper pilots, were awake during the perilous wee hours of Nov. 14. None in the national government—save Vice President Leni Robredo—lent a hand to recover the poor Cagayanos trapped on rooftops that cold night.

As of this writing, Typhoon Ulysses’ death toll has risen to 69, with 12 people still unaccounted for.

It is true from evidence, therefore, that the students of Ateneo have all the right and the reasons to launch their academic strike. Government response leaves much to be desired, forcing the students’ hands to risk their own chance at a good education to help their fellow students and professors who fell under the grip not only of recent catastrophes but government inaction.

And Ateneo leading the call, with UP dragged in the middle of the fray, doesn’t come at all as a surprise. These two universities and many others have since the 1960s paved the way for student mass action to change the course of the country’s history.

To quote Miguel Paolo P. Rivera, a lecturer at the Department of Political Science of the Ateneo de Manila University, on the need for student protest actions during trying times:

“Protests are not simply the expressions of one’s disagreement with a piece of legislation or the policy direction of government. What a demonstration makes possible is a space where people can create and maintain the constitution of individuals as a political community, that is, as human beings acting in concert with one another, to borrow the words of 20th-century political theorist Hannah Arendt. It establishes and imagines another world, one that insists upon an alternative that falls outside of current configurations of political realities. It rethinks institutions and parliaments where, especially in the Philippine context, legislators and leaders are often more comfortable with wheeling-and-dealing to perpetuate themselves in power than in genuine forms of discourse and public service.”

He adds, “Dissent and protests have many forms, be they gatherings on city streets or nationwide marches on foot towards the country’s seat of power, or even students researching the causes and roots of our world’s predicaments with the aim of educating their fellow citizens. These forms of protests are essential and much needed in our democratic society. Indeed, protests fulfill its promise only when it attests to the fullness of humanity — when human beings in their individual rage, tiredness, meekness, and poverty choose to constitute themselves as a humanity acting in concert, imagining and fighting for a better world for each other. It is a rejection of the narrow-mindedness that our leaders or even we ourselves sometimes show.

“To protest, therefore, is to refuse to accept that in our times, we have no other choice.”

Government will do everything in its power, spend all that its resources can offer, to convince us that we are left with no choice but to bear the brunt of State incompetence. To fight, therefore, is to show government that it is lying, that we do have a choice—and that choice is ours to make by constitutional right.

I am thankful to the country’s youth for showing us where our choices lie: in open dissent, protest action in all its shapes and forms, in airing our grievances in ways that capture government’s attention.

The poet Henry David Thoreau has something to say about this: ““Disobedience is the true foundation of liberty. The obedient must be slaves.” #WeWillNotBeSlaves

Joel Pablo Salud is an editor, journalist and the author of several books of fiction and political nonfiction. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official editorial position of LiCAS.news.