If yesterday’s State of the Nation Address (SONA) failed to make your blood boil, I suggest you take your pulse.

Nothing can be drearier, altogether foreseeable, and quite the sorry piece of drivel designed either to further annoy a restless public or provide ammunition for trolls long starved of something new to say.

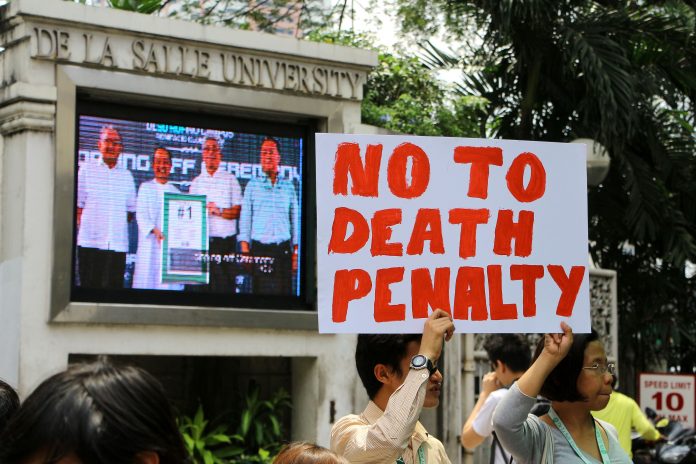

But that’s the thing: there was nothing new in what the president said in all of an hour and a half, save perhaps the passing familiarity of a bill Duterte and his cohorts have been meaning to pass since the beginning of his term: the reinstatement of the death penalty.

One too many deaths

After four years and tens of thousands of deaths via a bogus drug war and a long string of vigilante activity, it seems Duterte has yet to give up on this pipe dream.

The failure to push the bill hinged on earlier moves by former President Gloria Macapagal Arroyo to oppose any mention of the death penalty when she served as Deputy Speaker of the House of Representatives in 2017.

Despite threats from former House Speaker Pantaleon Alvarez that anyone who’d oppose the death penalty bill would be stripped of leadership in Congress, still Deputy Speaker Arroyo stood her ground.

This wasn’t anything new. As president in 2006, Arroyo signed Republic Act No. 9346 together with former House Speaker Jose de Venecia and then Senate President Franklin Drilon, fully abolishing capital punishment.

The Senate likewise wasn’t too keen on passing the said bill. In 2019, calls to reinstate capital punishment came by way of two of Duterte’s closest allies in the Senate: Ronald “Bato” dela Rosa and Christopher “Bong” Go.

Senate Minority Leader Franklin Drilon, however, argued against it by citing the country’s “weak justice system that is prone to error”.

Heinous crimes

During the House debates on House Bill 4727 in early 2017, a bill seeking to reinstate capital punishment for 21 heinous crimes, opposition lawmaker and Albay 1st District Representative Edcel Lagman came out with a list of compelling arguments against it.

Lagman, if you recall, was the principal author and sponsor of Republic Act No. 9346, the law which repealed the death penalty.

Lagman said, “We must put the death penalty bill irretrievably in the backburner and address and implement with dispatch much delayed reforms in the police and justice systems […] It will not make the revival of the death penalty less retrogressive and repugnant to the inviolability of life if it is imposed solely on drug-related offenses. In fact, the Philippines is a State Party to the 1988 UN Drug Convention which prescribes only imprisonment, not death, to drug-related offenses.”

His reasons included erring, rogue cops (citing the police murder of a Korean businessman), corruption in the judiciary, officers involved in the drug war killings, international jurisprudence, the Declaration of Rights and Duties of States as adopted by the 1949 International Law Convention, and “pronounced social injustice, crippling poverty, and utter absence of quality of life among the disadvantaged and marginalized sectors,” among other things.

Double whammy against human rights

Human Rights Watch (HRW) echoed the speech of Rep. Lagman, highlighting vigilante activities and human rights suppression as primary reasons to seriously rethink the re-imposition of capital punishment.

“Coupled with the Duterte administration’s brutal ‘war on drugs’ in which police and unidentified ‘vigilantes’ have killed nearly 8,000 people since last July, the passage of this law would represent a double-whammy against human rights in the Philippines […] Adding a veneer of legality to the bloodbath in the Philippines will make stopping it even harder,” the group said.

Capital punishment and the child offender

Amnesty International (AI) took the debate a step further by saying that capital punishment is a symptom of a culture of violence, not a solution to it.

“The death penalty is the ultimate cruel, inhuman and degrading punishment,” the group said. “Amnesty opposes the death penalty in all cases without exception—regardless of who is accused, the nature or circumstances of the crime, guilt or innocence or method of execution.”

The group’s mission to track down executions anywhere in the world led them to varying cases of death sentences imposed on juveniles. This is clearly a serious breach of international laws.

Based on its 2019 Global Report on Executions, “Since 1990 Amnesty International has documented at least 149 executions of child offenders in 10 countries: China, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Iran, Nigeria, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, South Sudan, Sudan, the USA and Yemen.”

It added: “China remains the world’s top executioner—but the true extent of the use of the death penalty in China is unknown as this data is classified as a state secret; the global figure of at least 657 recorded in 2019 excludes the thousands of executions believed to have been carried out in China. Excluding China, 86% of all reported executions took place in just four countries—Iran, Saudi Arabia, Iraq and Egypt.”

History’s carnival of horrors

Based on an article in Vera Files by Joel F. Ariate Jr., a university researcher at the Third World Studies Center, College of Social Sciences and Philosophy at the University of the Philippines, Diliman, the Philippines is no stranger to the death penalty in the past.

“Based on the accounts of 16th- and 17th-century Spanish priest chroniclers like Francisco de Santa Ines, Juan Francisco de San Antonio, Joan de Plaçençia, and Francisco Colin,” Ariate wrote, “indigenous Philippine society practiced the death penalty”.

“The condemned can be tied to a post and speared or whipped to death, hanged, or simply stabbed by the offended party as authorized by the village chief […] But distinct in imposing death as punishment in early Philippine societies was the chance given to the culprit to negotiate his or her way out of it. One can settle the penalty of death by either paying in gold or making one’s self a slave to the offended party.”

Ariate mentioned one interesting case which may mirror all cases: the Basi Revolt during the 1800s in Ilocos Norte against Spanish colonials. At the time, the heads of conspirators were severed and placed in cages for public display. This “theater of the macabre” colonial Spain used to cripple any attempt by conspirators to launch an uprising against the Spanish monarchy—including beheadings and the garrote, all done in public.

However, he said, “the Filipinos seemed to keep on failing to learn the lesson of the gallows and of mutilated corpses not to revolt against Spain.” For all intents and purposes, the show of cruelty did not stop Filipinos from revolting against the colonizers.

Capital punishment is obviously a brutal relic of colonial cruelty, if not evidence of the darkest recesses of the human condition. But as history has shown, it was never a deterrent. Not against crime. Not against dissent. Not against revolution. Our country’s revolutionary and heroic legacy is proof of this.

If anything, capital punishment might just be the spark to stir up a long-awaited awakening. For what else can a man or woman do, one who has been stripped of everything, one with nothing to lose?

Joel Pablo Salud is an editor, journalist and the author of several books of fiction and political nonfiction.