They call it “kalinga,” the Filipino word for “care” or “gentle nurturing.”

In today’s Philippines, however, euphemisms often herald abuse, the thumps of boots, and armed men sweeping to enforce dictates that spin as fast as the whims of the country’s ruler.

“Kalinga,” as unveiled by Interior and Local Government Secretary Eduardo Año, is a house-to-house search for carriers of COVID-19, which has infected close to 60,000 people in the country.

It also represents a forced trip to isolation centers.

To care is to squeal on your neighbors, according to the newest containment gospel from the former Army chief.

It is a surreal, illogical demand. Congress gave President Rodrigo Duterte powers to align the national budget to deal with the health emergency. The Health department’s US$909 million budget to manage the pandemic includes testing and contact tracing. Health officials explain a results backlog of more than 10,000 tests by citing the need to vet the locations of potential and confirmed carriers.

Why need a sweep of neighborhoods when you have a grand database?

The new policy follows a surge in infections since the government eased a general lockdown to reboot a languishing economy. Duterte and his aides have blamed citizens, ignoring the lapses that shoved vulnerable sectors into the pandemic maelstrom.

Lower quarantine levels came with a halt to social amelioration, which was already saddled by cracks. People had to scurry for livelihood and jobs with slashed wage rates. They found a dearth in safe transportation.

The disease has infected close to 200 staff of the capital’s train service, including frontline ticket sellers. Buses ran at 30 percent capacity. Jeepneys, the backbone of the capital’s transport system for the poor, were left stranded absent of rhyme or reason.

The government also refused to pay for or even subsidize the testing costs of the returning workforce. Hard-up businesses fell back on cheaper, less accurate anti-body tests.

Repatriation services for returning overseas workers were chaotic, with destination provinces reporting infections among arrivals. Then the government launched a program to return 7.3 million newly jobless citizens, 17.7 percent of the labor force, to their provincial hometowns.

The campaign featured hiccups that forced masses of citizens to huddle for days on wet streets or damp sheds, or in sweltering tents.

Almost all provinces have since reported new COVID-19 cases where there once were none; most trace back to the repatriation program.

The Duterte government, with its allergy to accountability systems, naturally blames the victims of its failures.

Victim-blaming tries to hide the incompetence of planners who spent big money for quarantine infrastructure but refused to shell out the needed funds for health personnel.

The Health department initially called for “volunteers” at a time when the country became Asia’s biggest casualty rates for front-liners due to delayed delivery of protective gear.

Then authorities rolled out a program for temporary hires, although pre-COVID blueprints had permanent hiring benchmarks to bring down a critical gap in ratio of health workers to population.

The government refused to test people unless they had clear symptoms, a policy that included health workers with known exposure to COVID-19.

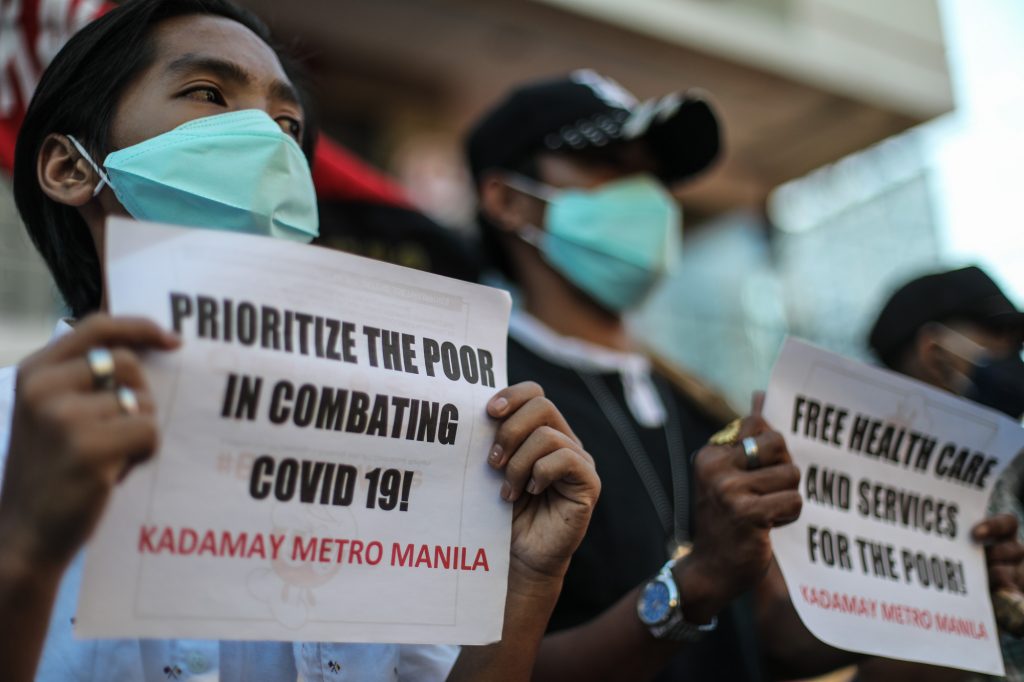

Family members of people who died from COVID-19 did not get tested until they, too, fell ill. Critics repeatedly called for mass testing of vulnerable sectors, including poor communities with COVID-19 cases but the government refused to listen.

A full month into the easement period, the Health department is just preparing testing policies for the labor force. Who pays remains anybody’s guess.

The only thing clear is, if you get sick, you become the enemy.

Duterte’s office says critics are fear-mongering. But Filipinos have learned there is no ceiling for this government’s capacity for mayhem.

Four years ago, Duterte ordered police to go house-to-house to ferret out drug users and pushers.

“Tokhang,” conjured scenes of neighborly intervention — polite knocks inviting people to start a new life.

Emily Soriano, a village security volunteer in an urban poor community in Quezon City, believed Duterte’s promises of rehabilitation and livelihood assistance. She led police to the homes of users. Her hopes for peace soon turned into a nightmare.

Police forced confessions and then tracked down and killed close to 6,000 in sanctioned operations, with a corps of vigilantes killing triple that number. Those who claimed to have no links to illegal drugs were asked to list neighbors — or else.

The truth of “tokhang” ripped through the Soriano home on Dec. 28, 2016, when authorities killed 15-year old Angelito and seven of his friends. They were “collateral damage” in a chase for a “suspect” who later emerged as a police informer.

For families scarred by death via “tokhang,” the new community COVID-19 round-up resurrects all the horrors of the original purge.

The target communities are largely poor, with crowded homes crushed against each other — the very same villages that chalked up the biggest numbers of “tokhang” killings.

Duterte blamed the poor for the drug scourge and fulfilled his vow to make them pay. He attacked experts who called addiction a health problem, or critics who pointed out that many of the police doing the killings were also suspected to be in bed with drug gangs.

It’s the same recipe all over again.

Disobedient, stubborn, recalcitrant — the government uses a lot of adjectives for people falling between the cracks of its US$4 billion health emergency program.

The hunt for the sick is led by a police officer who flouted health guidelines at a birthday party: lawmen stuffed masks into pockets as they chugged banned alcohol and crowded around an equally banned buffet.

In Duterte’s world, there are no innocents.

Inday Espina-Varona is an award-winning journalist in the Philippines. She is a recipient of the “Prize for Independence” of the Reporters Without Borders in 2018. The views expressed in this article are the opinions of the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial stance of LiCAS.news.