SHE died waiting for help. She died dreaming and hoping that all would be well in the end. She died wanting to see her children back home in the province.

In the Philippines, people say that one’s eyes can turn white of waiting. For some, it’s a joke, sometimes a subtle rebuke for those who arrive late.

For those who have heard of the story, and untimely death, of 33-year old Michelle Silvertino, it’s not funny, however.

On May 31, a day before Manila eased quarantine restrictions, Michelle, a domestic helper in the outskirts of the capital, asked permission from her employers to be allowed to go home.

She wanted to be with her children and her family in Bicol, eight hours away from the capital, in the midst of the uncertainties brought about by the coronavirus pandemic.

The mother of four had tried to catch a bus to her home in Calabanga, Camarines Sur province, in the Bicol region — more than 400 kilometers southeast of Manila.

Michelle left her hometown last year with a dream to send her four children — with ages between 11 years and three years old — to school. She was a single mom.

She left behind the cornfields, where she worked, hoping to fulfill a dream. She came to Manila, wishing that luck would land her a job as a domestic worker abroad.

Unfortunately, she was declared “not fit to work” because of “fluid in lungs.” But there’s no stopping Michelle. Instead of going home, she stayed and worked as a maid in the city.

Last month, she insisted to be allowed to go back home to Bicol and asked her employers to drop her in a nearby bus station.

Realizing that there were no available transportation because of the lockdown, Michelle walked for three hours to another bus terminal, hoping that she would find a ride home.

She walked from Quezon City, north of Manila, to Pasay City in the south, with hopes of catching a ride from there.

But there was no bus in the station. There was nothing. Michelle decided to wait. She waited on a bridge along a highway. She waited for five days.

Government personnel who sweep the streets of the homeless thought Michelle was a street dweller and asked her to leave.

Michelle told them that she was just waiting for a bus. They allowed her to stay and to sleep on the pavement.

The next day, the city mayor sent his men to check on Michelle’s health. The mayor’s men said Michelle was just tired and left her on the bridge.

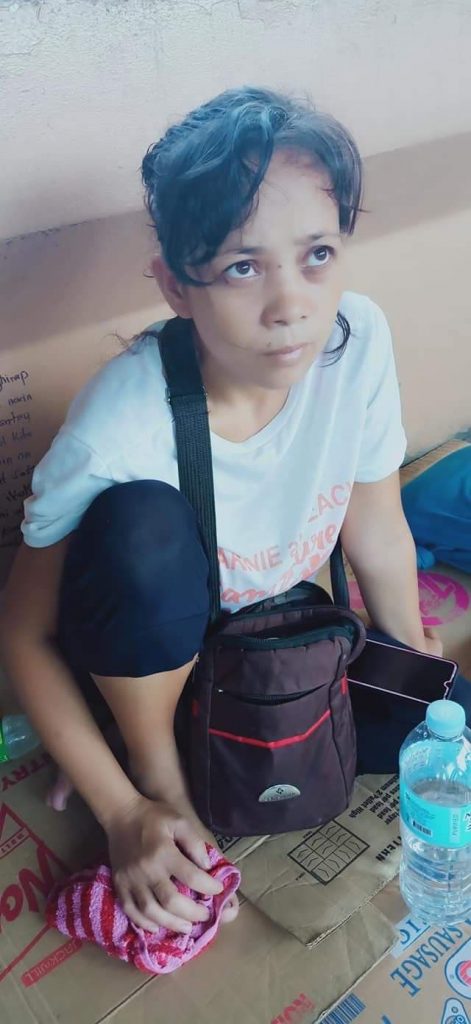

On June 3, Jhimbo Mojica, one of the street clearing operatives, talked with Michelle. He took a photo and posted the woman’s ordeal on social media.

Michelle’s story reached the office of Adrian Martinez, officer-in-charge of the office tasked to help stranded individuals in the city, who helped her get a bus ride to Bicol

Michelle was scheduled to take a coronavirus test, a requirement for all travelers, on June 6.

Jhimbo said Michelle was excited when they spoke over the phone on June 4. Finally, she would see her children again.

An hour later, Jhimbo received a message from a police officer, saying they were bringing Michelle to the station to give her shelter from the rain.

At about two o’clock in the morning, Jhimbo was again told that the police officers were bringing Michelle back to the bridge because she was “crying and couldn’t breathe.”

At four o’clock in the morning, Jackie, a homeless street dweller, informed village officials and police officers that the woman known as Michelle had high fever. The officials ignored Jackie.

“Dedma,” said Jackie, referring to the officers’ reaction. “Dedma” is a street slang for feigning ignorance.

When Jackie and other street dwellers saw Michelle was already unconscious, they, who were described by the police in its report as “concerned citizens,” ran to the station to inform about Michelle.

It was only then when the police rushed Michelle to a hospital where she was pronounced “Dead on Arrival.”

Michelle’s death certificate shows that she was a “probable” case of the new coronavirus disease.

The money she saved for her family, about US$110, was gone.

“[Her] case is a testament to the Philippine government’s gross incompetence and indifference,” read a Twitter post by activist Rauff Sissay.

Women’s right group Gabriela lambasted the government’s “criminal neglect” of the poor amid the pandemic.

Days after her death, the government’s Social Welfare department announced that it had delivered a US$300 “subsidy” to Michelle’s mother, Marlyn.

News about Michelle’s death alerted the government to the plight of at least 228 people who were staying under a bridge while waiting for transportation back home.

One of them, Dennis Sebastian, was supposed to be on his way home to Pagadian City in the southern Philippines in time for the graduation of her daughter last March.

He worked in Tuguegarao in the northern tip of the island of Luzon. He traveled to Manila for the flight home but was stranded in the capital due to the lockdown.

For three months, Dennis stayed in a village hall in the capital.

He already sold his mobile phone, his luggage, and even a pair of shoes for US$10 to survive his days in the capital. There were days, he said, that he just had to cry to forget his hunger.

On June 4, the 54-year old walked to the airport to finally catch a flight home. But the planes were not flying that day.

He joined the other stranded people under a bridge outside the airport to wait for their flight home.

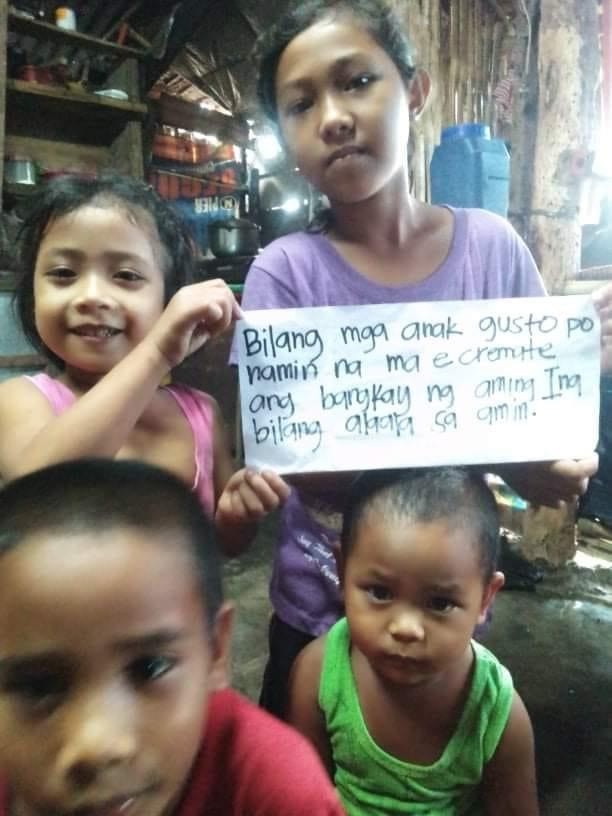

A day after Michelle’s death, a photo of her children holding a sign asking for help to have their mother’s body cremated and brought home went viral on social media.

The local government, however, had already buried Michelle in a body bag in a shallow hole in the city’s public cemetery with her name etched on concrete.

Philippine laws do not allow the exhumation of a body immediately after burial.

The children have to wait for at least three more years before their mother, the ashes of their mother, can go back home.

Like Michelle when she was still alive, the children have to wait.