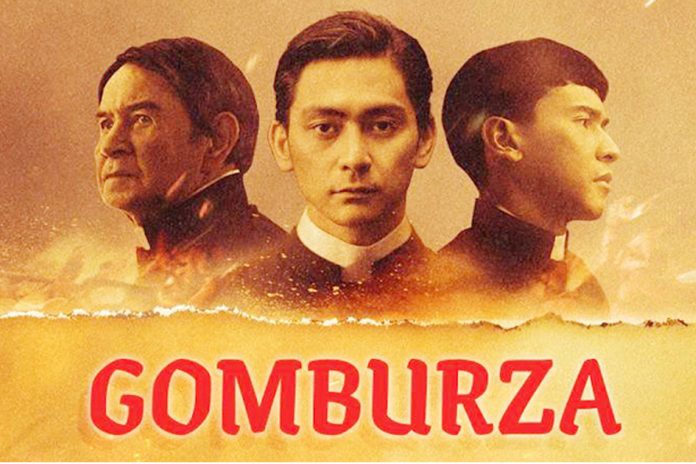

Theatres across the country today are still showing the film GOMBURZA – the historical biographical film co-written and directed by Pepe Diokno – that features and follows the lives of the Gomburza, three Roman Catholic native Filipino priests executed by garrotte during the latter years of the Spanish colonial era in the Philippines on February 17, 1871, in Bagumbayan.

Produced by Jesuit Communications, MQuest Ventures, and CMB Film Services, it serves as an official entry to the 49th Metro Manila Film Festival and was released in cinemas nationwide on December 25, 2023.

On its first days of showing, the film could not compete with the more popular entries, with only a few audience inside the theatres. A few theatres that showed it beginning December 25, pulled out the film after just a few days.

When I went to see it on December 27 in Cebu, only one cinema was showing the film and there were only more than ten of us in the audience. Then the MMFF 2023 awards were announced on the evening of December 27.

GOMBURZA won most of the important awards including 2nd best Picture and in the following categories: Director, Actor, Cinematography, Sound, Production Design, and the Gatpuno Antonio Villegas Cultural Award.

The awards plus positive reviews in both mass and social media, as well as word-of-mouth feedback, encouraged more people to face the inconvenience of facing the traffic in the streets and having to pay for exorbitant-priced tickets.

More theatres began to exhibit the film. A friend took me to see the film for the second time on December 30 and there were more than a hundred of us in the audience. Across the country, it was reported that audiences clapped at the end of the film to show their appreciation.

Indeed, the film should be seen by all Filipinos, especially the millennials and Gen-Z generations who hardly know about the role of Gomez, Burgos, and Zamora in giving birth to the rise of a “Filipino” consciousness which ultimately led to the founding of the Republic of the Philippines and we, its citizens, now known worldwide as Filipinos.

All Pinoy students who are enrolled in Philippine History classes should have the opportunity to view this film (as were the films General Luna, Goyo, and the bio-pic of Hermano Pule). Unfortunately, the film is showing now in cinemas while schools are on their semester break.

One hopes that the film will still be showing when the second semester begins in early January. Otherwise, the film’s producers should make sure to have this film available for film showing the colleges and universities at a price affordable to students.

While I agree with practically all the positive reviews that have appeared primarily in social media – which is why I am not writing a review of this film as it would only be redundant – I do have a few comments and questions regarding the content of the film.

There is even a question for the jurors of MMFF 2023: how come despite winning the major awards, GOMBURZA was only considered 2nd best film (when Firefly was adjudged Best Picture only had two awards)?

GOMBURZA’S screenplay was co-written by Rody Vera, Ian Victoriano, and the director himself, Pepe Diokno. They were certainly helped by Fr. John N. Schumacher S.J.’s seminal work – Revolutionary Clergy: The Filipino Clearly and the Nationalist Movement (1850-1903). There were other Jesuit historians, e.g. Fr. Rene Javellana SJ, who were also consulted.

The major hurdle faced by the writers would have been how to tell the epic story of the three Filipino priest-martyrs within a two-hour time limit (in fact the film was less than two hours by ten minutes). And to think that it begins with the story of Apolinario de la Cruz, otherwise more popularly known as Hermano Pule, culminating in Jose Rizal’s execution and then the outbreak of the Katipunan revolution.

Naturally even as the film helps to enlighten the not-so-knowledgeable viewer as to the various aspects of the priests’ life that led to their martyrdom, nonetheless, a lot of questions would still arise. It is not fair, of course, to expect the filmmakers to be able to present all the backstories that explain all the scenes included in the film.

Given the limitations of time and resources, they needed to focus the flow of the story as tightly as possible and thus, avoid unnecessary details.

This is why, Philippine History teachers must find a way to discuss the film in class to fill in the gaps. The teachers can assign their students to do more research to trace the needed back stories and explain scenes in the film that did raise a lot of questions. These include the following:

1. While not as known as the three martyrs, Padre Pedro Pelaez nonetheless should have a pride of place among our recognized heroes. Just because he was not martyred – and died because of an earthquake – does not make him a less hero than the three priests. After all the film seems to credit him as having first coined the term “Los Filipinos.” As the mentor of Padre Burgos and compatriot of Padre Gomez, he was the first to articulate a “nationalist consciousness.” Who was he really and what brought him to his advocacy for secularization and equality for Filipinos?

2. How did the term “Filipino” arise? Was Fr. Pelaez the first one who coined it? Rizal first used the term “Katagalugan” rather than Filipino in his first writings and yet he is considered the First Filipino and the Father of Filipino Nationalism. It is a term which can be considered an artificial construct. This explains why there is a scene in the film when an Indio servant is asked if he is Filipino and answers that he is Tagalog. The term Filipino only arose in the last stage of the Spanish colonization. Before that, we were Tagalogs, Ilokanos, Cebuanos, Maranaw, Tausog, Tboli, Subanen, and more than a hundred ethnolinguistic peoples across the archipelago. Benedict Anderson’s “Imagined Communities” theory can help explain how an artificial construct has now become an accepted term to refer to our national identity.

3. Fr. Pelaez is credited in the film as having given rise to the secularization movement. Just what is this movement all about involving the secular priests like the three martyrs? Patronato Real is also mentioned in the film as being linked to why there was a difference between being a secular priest and those who were considered friars. What was this Patronato Real all about that led to the distinction between the two? Why was the focus on the struggles between the two groups in the Antipolo parish (the suggestion was that the parish had a higher income than the others)? There were broader reasons why there was conflict between them including other various forms of discrimination against the criollos and especially the native Filipino priests (Hermano Pule’s rejection to join the religious congregation made that clear at the start of the film). One only has to read Schumacher’s book to understand why the Iglesia Filipina Independiente was founded by Gregorio Aglipay, in the context of the Spanish friars’ prejudice against Pinoy priests.

4. The term “criollo” was often heard in the film to refer to the three martyrs. A criollo was a full-blooded Spaniard born in the Spanish colonies in Asia and the Americas. Its synonym was being an Insulares. It differentiated them from the peninsulares or full-blooded Spaniards born in Spain and mestizos who were the offspring of Spaniards who had children with native women. Those of indigenous ancestry were referred to pejoratively as Indios. So originally the film’s main characters referred only to the criollos as Filipinos. Was the class differentiation related more to the place of birth and racial characteristics rather than other elements? And how did eventually the term Filipino encompass everyone: criollos, mestizos, and Indios who would embrace the idea of “national consciousness?”

5. There is an interesting scene when the children are showing the moro-moro shadow play when a friar says in reaction to what happened to the three martyrs (to paraphrase): “History will not be kind to us friars. Do you think they will blame Izquierdo? Or Spain? No, they will blame the friars!” I wonder why the writers thought it important to include this scene. Of course, it is not true that we have reasons to demonize all the friars for the conduct of their ministry and life witness during the entire Spanish colonial regime. For there were some of them who led exemplary missionary lives (e.g. Fr. Saturnino Urios in Mindanao).

In fact, at the height of the abuses committed against our ancestors, there were attempts to curb the abuses of both the secular rulers and the friars influenced by the writings of the Dominican activist and social reformer, Bartolomeo de las Casas, who actively campaigned for the natives’ human rights across the Spanish empire. Still, in general, the friars were complicit with the colonizers’ human rights violations against our ancestors. A question begs to be asked about this scene in the film: Are the words uttered by this friar a form of apologia on behalf of the five friar congregations who took an active part in the Spanish occupation of our archipelago?

6. To what extent were the three friars truly revolutionary? The film shows clearly that Padre Zamora was hardly in the same league as Padres Pelaez and Burgos; one could say he was just an unfortunate person who was in the wrong place at the wrong time (in the vernacular we refer to him as “nasabit lang.”) In fairness, however, he did offer his life like the two other priests, albeit reluctantly. But can they be considered as revolutionary as other contemporary priests (including the likes of Camilo Torres of Columbia who joined the Ejército de Liberación Nacional and died as a rebel in 1966 or our own Conrado Balweg who founded the Cordillera Liberation Army and died in 1999 and Fr. Frank Navarro who was an NPA rebel who died in 1994). But because the three martyrs – like Rizal – did not opt to carry arms, would they still be considered true revolutionaries?

7. The film begins with the insurrection led by the peasant Hermano Pule and ends with the KKK whose foot soldiers were mainly peasants. The first and last scenes served as book-ends to help explain the genesis and the final phase of the KKK-led Philippine National Revolution where the main protagonists were peasants, led by charismatic leaders such as Pule and Bonifacio. However, GOMBURZA dealt more with the revolutionary fervor among those who were the more privileged segment of the population, namely the secular priests, the Illustrados, and students. The film’s Indios are only seen in the background like one of the servants who eavesdrop in many conversations and eventually is seen outraged at the execution site and later as a Katipunero. This begs a question that continues to be debated especially from a Marxist perspective: who are truly the ones who would radically change society’s oppressive structures? The proletariat or the petty bourgeoisie?

8. There are unexplained scenes that need to be further discussed. These included: why Rizal’s mother was arrested and what happened to her later on, how to explain the behavior of the father of Paciano and Rizal, how the Cavite mutiny arose, what is the connection between the Cavite mutiny and the one at Fort Santiago, how come the “Filipino” bishops did not pro-actively intervened to stop the execution of the priests (there is, however, a scene where one of them asked Isquierdo that they be allowed to wear their cassock) and many other questions. One can tell that class discussions on these questions can be quite enlightening and will help appreciate the film even more.

9. Feminists viewing the film would certainly ask: where are the women in this narrative? The only significant scene showing the women’s role in this struggle was the arrest of Rizal’s mother. Nuns appear in the scene but they hardly have important roles to play. Would the fact that the writers and consultants were all male have been a factor that contributed to this oversight?

10. Lastly: to connect the priests’ martyrdom and the reality of the Philippine Church today – a question may be asked: “Where are our secular (or diocesan) priests today about the issues bedeviling the Filipino people, in a context where there are still neo-colonial forces that continue to make life miserable for the majority of the citizens? Are there still a Pelaez, Gomez, and Burgos among them willing to risk their lives to advance justice, freedom, and equality? Has this nationalist legacy been passed on to them? During the height of the Marcos martial law regime, there were signs that this legacy was alive. But how is it these days?

The above questions, however, are not meant to downgrade the importance and relevance of GOMBURZA. And it is not a surprise that critics and netizens have all praised this film to the heavens! It is indeed a stunning, remarkable film that demands a huge audience across the country and overseas wherever there are Filipinos who are still estranged from the notion of being part of a Philippine Republic. And those whose knowledge of Philippine history is mainly about Magellan, Lapu-Lapu, and Marcos.

A film is not expected to compete with history books but as one critic wrote, it can serve a purpose in nation-building through a medium that can both be enlightening and also “entertaining.” It takes a truly gifted filmmaker – and Pepe Diokno with GOMBURZA has shown he could go the way of Ishmael Bernal, Lino Brocka, Lav Diaz, et al – to make a film that can provide lessons of history (“so we will not repeat the same mistakes”) and make us shed tears and yet clap our hands at the end of a film!

Karl Gaspar is a Redemptorist brother whose works focus on grassroots development, Indigenous Peoples’ rights, interfaith dialogue, peace, and ecological concerns. During Martial Law, he was detained for 22 months by the military, and adopted by Amnesty International as a political prisoner, strengthening his commitment to peace and freedom advocacy. He is a multi-awarded author who is now based in Cebu.