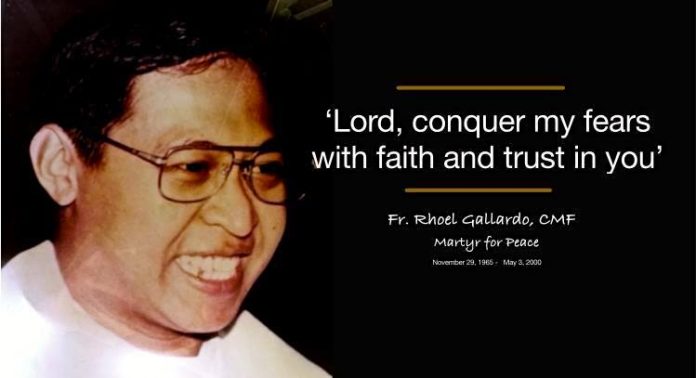

On May 3, 2000, Claretian missionary priest Rhoel Gallardo, a quiet, simple missionary died in a crossfire between the bandit Abu Sayyaf group that abducted him and Philippine soldiers, who tried to rescue him, on the island of Basilan in the southern Philippines.

The priest had been held in captivity since March 20 that year, along with some teachers from a Catholic-run school in the village of Tumahubong in Basilan province.

This is an excerpt from the book “Into the Mountain: Hostaged by the Abu Sayyaf” written by LiCAS.news editor Jose Torres Jr.

For four days and five nights they walked, without eating. They forged their way downhill and then up again, avoiding the sharp rocks and the open roots. They marched in the dark, the rough stones cutting into their feet, the thorns penetrating their clothes, the mosquitoes and leeches feasting on their blood.

They rested during the day, to avoid being spotted by pursuing soldiers, and they marched the whole night, as though wild animals were chasing them.

“Walk, Father, walk. Rest will come soon,” a bandit prodded Father Rhoel from behind as someone else tugged at the rope that was tied around his waist.

Then one of the bandits signaled everybody to stop. The children — tired, sleepy, and wet — wasted no time and dropped to the ground. The older ones moved more slowly, reclining on tree trunks. Even the bandits, hungry and muddy as the rest, were weary. All were wet from the dew and from last night’s rain. There seemed to be no stopping the rain in the forest.

After a few minutes, Ustadz Nur, the bandits’ “operations officer,” ordered everybody to stand up. “We have to move before they come nearer,” he said. Ustadz Nur had been a public school teacher in Basilan before he joined the Abu Sayyaf.

“Do you know what you’re doing?” Abu Amira, the medic, asked, within earshot of Mr Rubio and other hostages. “Everybody’s tired and we’re not getting anywhere. Where are we heading, anyway?”

“Shut up, Amira,” Ustadz Nur answered angrily. “I know what I’m doing.”

“If I only knew beforehand that we would just walk around and around the forest, I would have not joined this operation,” Abu Amira complained. “Abu Hasser and I could have asked Khaddafy for a vacation.” Abu Hasser was Abu Amira’s younger brother.

“We’re useless in this operation,” the teenage Abu Hasser murmured. “We’re medics and there are no sick people here.”

“Do you really have plans for us?” Abu Amira confronted Ustadz Nur. “You’re just getting us killed.”

“Shut up, the two of you!” Ustadz Nur shouted. “Just get up and walk.”

The stragglers resumed marching. It was Wednesday, May 3.

At around 6 a.m., Ustadz Nur decided to stop. The hostages lay down on the wet grass, ready for a long rest. The day was starting to turn bright, the sun’s rays beginning to penetrate the damp forest.

They had rested for barely 15 minutes when one of the bandits came running back from the front, ordering everybody to move back. “Slowly, move back. Don’t stand up, just move back,” he ordered in a low voice, almost whispering.

“Something must be wrong,” thought Mr Rubio, who was toying with a stick. “The military must be nearby,” he whispered to Rodolfo Irong, a teacher from Sinangkapan Elementary School, who was sitting beside him. They retreated slowly until they felt their backs pressing against the trunk of a mango tree. Both closed their eyes, resting and thinking of their ordeal.

It had been exactly 45 days since they were kidnapped by the Abu Sayyaf.

Several times during their stay in Mount Punoh Mahadji, the male hostages talked about escaping, especially when they heard from the children that the bandits were planning to hack the older men to death. But they changed their mind after teacher Rosebert refused to join them. “I can’t come with you,” Rosebert said. “My wife Lydda is here and I don’t want to leave her behind.” Nobody argued with him.

Another time they heard rumors that the teachers would be released.

Excitement filled them, but their joy was short-lived, after Father Rhoel talked to the bandits and pleaded for the release of the children instead. The priest also insisted that if ever the Abu Sayyaf released the hostages, he would go last. He was a priest, he said, and he had nothing to lose.

“I will never forget him,” Mr Irong said to Mr Rubio once.

“Who?” asked Mr Rubio.

“Your friend, the priest,” Mr Irong answered. “He’s something.”

In their six weeks on the mountain, everybody noticed how Father Rhoel spent his time praying. Most of the time, he prayed alone and fervently. Nobody heard the priest complain. At times, he even skipped his food and gave it to the children. And he was always optimistic, confident that everything would turn out fine.

Mr Rubio was planning to hide under the thicket until it was safe. He saw some bandits pass behind him. Later, the soldiers came back. “Secure the area, secure the area,” a soldier shouted. Mr Rubio remained where he was. “Maybe I will die here,” he thought. But he saw no blood on his clothes. “I will live,” he said to himself.

“Secure the area, secure the area,” he heard the soldier again.

“I am safe. The military is here,” Mr Rubio thought.

“Sarge, I’m here. I am a hostage,” the school principal shouted.

“Stand up,” someone shouted back.

“I cannot stand,” Mr Rubio answered.

“Stand up,” a soldier shouted angrily.

“I can’t. I’m wounded. I’m Mr Rubio, the principal.”

“The principal is here,” someone shouted.

Armed men pulled him out of his hiding place. But almost immediately Mr Rubio’s fear returned, when he heard a former bandit, who had been integrated into the military, talking to the soldiers.

“Sir, this is my uncle. Sir, he’s my uncle. Sir, please, this man is my uncle,” the former bandit, who knew Mr Rubio from Lamitan, told a military officer three times. (Moros in Basilan call older men “uncle” as a sign of respect.)

While waiting for another helicopter to arrive and evacuate the dead and the wounded, the school principal sat near the soldiers who gave him first aid. Mr Rubio saw that an officer, a young lieutenant, was fuming mad. He was cursing the soldiers around him.

Fresh troops arrived a few minutes later in two armored tanks. Immediately, the young lieutenant rushed toward the officer inside the newly arrived vehicles. The lieutenant was carrying an M-60 machine gun, which he threw inside the tank. He called a soldier inside the vehicle who was carrying a 50-caliber machine gun.

“Give me that,” the young officer shouted, taking the soldier’s machine gun. He put it on the ground and dismantled it. He then stood up and shouted at the officer inside the vehicle. “Why are you bringing a gun without a firing pin?” He also threw the 50-caliber machine gun inside the tank. “Throw all these. These are useless.”

Then the helicopter arrived.

Mr Rubio told the soldiers that Father Rhoel was hiding in the bushes.

As the helicopters lifted off from Mount Punoh Mahadji to bring the wounded to the hospital, villagers in Tumahubong held a procession to observe the feast day of San Vicente Ferrer, their patron saint. Unlike previous fiestas, it was a solemn affair.

Their children were still on the mountain, and their priest, they feared, was being tortured; he was nowhere near to carry the censer that burns the incense.

The faithful sang songs and recited the rosary as they walked slowly around the village, the saint’s statue on the shoulders of four men, followed by the women and their flickering candles.

As the congregation made its way back to the church, the head of the statue suddenly fell over. Everyone gasped; the crowd shuddered. “It’s an omen,” an old woman said.

In Isabela, on the other side of the island, tears rolled down the cheeks of the blind woman Dolor. She had just seen another sign, another red mark, this time on the hands of Mr Rubio’s wife. “Let us pray,” she told those beside her.

Three days later, Chief of Staff Angelo Reyes of the Armed Forces of the Philippines visited Mr Rubio at the Infante Hospital in Isabela.

“How are you, Sir,” the general asked Mr Rubio.

“I’m fine, thank you,” the school principal answered. “Where are the other hostages?”

“They’re in the hospital in Zamboanga,” General Reyes answered. “The priest was not fortunate.”

Tears filled Mr Rubio’s eyes. It was only then that he realized the worst had happened. Father Rhoel had not made it.