When the Philippine government and the rebel National Democratic Front declared separate ceasefires for the duration of the Christmas and New Year holidays, hope was rekindled that the two sides could once again face each other across the negotiating table rather than in the battlefield.

At the time, President Rodrigo Duterte had already raised the possibility of resuming the peace talks that started in 2016, but had been abruptly cancelled in 2017 following attacks by the New People’s Army guerrillas on government forces, even as the two sides were engaged in political negotiations.

But why is it that as of now, there have been no new developments on the backchannel talks approved by Duterte to pave the way for the resumption of formal negotiations?

Senator Christopher “Bong” Go was quoted by a recent news report that Duterte is still willing to resume peace talks, but gave no definite timetable.

Previous reports said Duterte wanted a one-on-one meeting with exiled communist leader Jose Maria Sison in Manila before formal talks could begin. But Sison reportedly wants the one-on-one to be held in Hanoi as he fears arrest if he decides to come home from Utretch in the Netherlands. This despite assurances from the presidential office that he would be immune from arrest if he flies to Manila.

Party-list groups identified with the mainstream left have been urging the Duterte administration to resume the peace talks with the NDF.

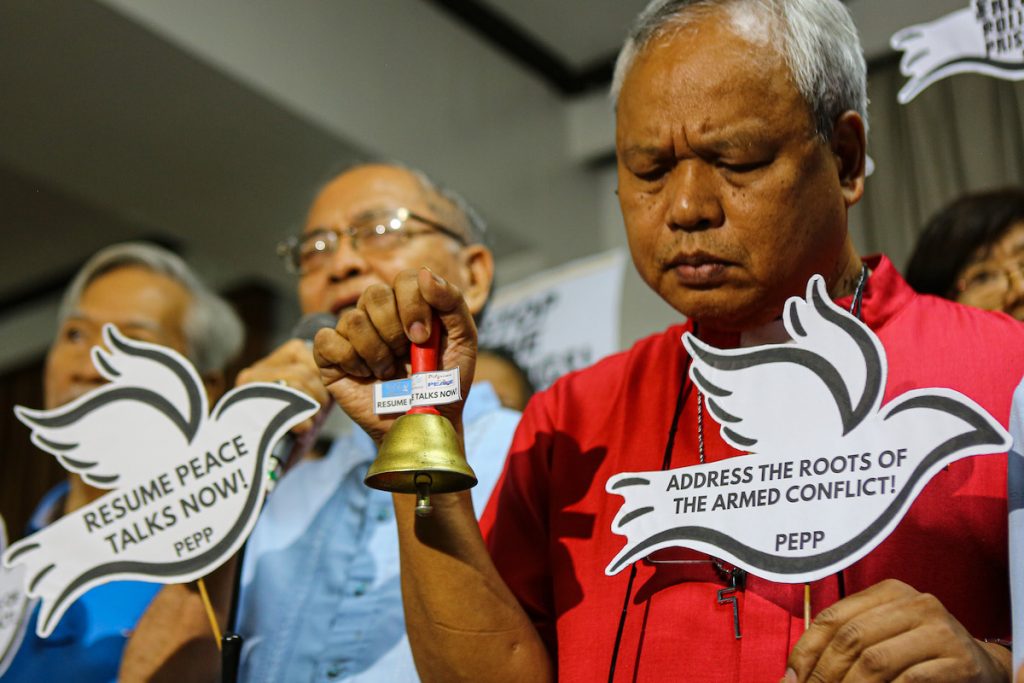

Then there’s the Philippine Ecumenical Peace Platform, composed of 110 Catholic and Protestant leaders from all over the country, which had expressed full support for Duterte’s call in early December to restart backchannel talks with the NDF to pave the way for the immediate resumption of formal talks.

“We vow to continue to use our faith resources and moral leadership to further expand the work of [the peace platform] throughout the Philippines,” said the group. “We will not stop and we will break the walls between religions and build bridges instead.”

The peace talks actually began in 1987 during the Cory Aquino administration, and were held off-and-on in the years to come.

Soon after he assumed office in July 2016, Duterte reached out to his former professor in college, Sison, also the founder of the Communist Party of the Philippines in 1968, and offered him an olive branch.

To show good faith, Duterte ordered the temporary release of rebel leaders who the NDF claimed were “peace consultants” so they could take part in the talks held in the Netherlands, with Norway acting as broker/mediator.

The talks were held without the benefit of a bilateral ceasefire. In other words, the military and the NPA were killing each other in the countryside even as the government and the NDF negotiators tried to make headway in putting a stop to the drawn-out conflict.

And there’s the rub. How can peace talks make any substantial progress when their armies are lunging at each other’s throats, while their political negotiators try to appear cordial and smile for the TV cameras amid discussions on proposed reforms that would end poverty and injustice that lie at the root of armed rebellion?

Why should the armed insurgency be ended at the negotiating table?

The fighting has raged in the countryside for the past 50 years, with at least 30,000 killed on both sides, and neither side poised to achieve military victory.

The military has the clear advantage in terms of manpower — around 150,000 personnel, if I’m not mistaken — and fighting capabilities, as it has jet fighters, tanks, and assorted heavy weapons to attack NPA bases in various parts of the country. But launching all-out war against the rebels could lead to collateral damage among the civilian population that the government obviously does not want.

On the other hand, the NPA remains a ragtag guerrilla outfit with only 3,000 fighters spread out in certain parts of the country, armed only with rifles, handguns, and landmines. It may have a large, popular base in some provinces, but certainly not enough for them to declare themselves independent territories with their own counterpart governments.

The NPA, led by the CPP, whose guiding ideology is Marxism-Leninism-Maoism, cannot launch big military offensives given its small number and limited firepower compared to the Armed Forces of the Philippines. In short, its bid to seize political power through the barrel of the gun appears doomed at this time.

What the CPP-NPA-NDF cannot win in the battlefield, it hopes to win via the negotiating table. That is why it insists that the peace talks focus on economic and social reforms, as well as political and electoral reforms, before cessation of hostilities and demobilization can be discussed.

The armed rebellion in the countryside acts as a drag on economic and social development. At issue is the sincerity of both sides in really ending the fighting.

Ernesto M. Hilario writes on political and social justice issues for various publications in the Philippines. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official editorial position of LiCAS.news.