Colors and other accompanying symbols play an important role in our political and social landscapes. They express our identity as a social group, help us protest against the present systems, or rally people towards an alternative vision.

Green is the color of environmentalism; purple is for the fight on gender; red is for socialist and communist ideals; blue is for right-wing conservatism, etc.

At the height of the Martial Law, yellow was the color of resistance.

In 1983 when Ninoy Aquino decided to come home, people tied yellow ribbons on the streets in the spirit of a 1973 hit entitled “Tie a Yellow Ribbon in the Ole Oak Tree”. The lyrics go “tie a yellow ribbon… it’s been three long years… do you still want me…” which was originally a welcome to US soldiers coming from Vietnam and Korean wars.

In the Philippine scene, the yellow ribbon was a welcome for Ninoy. When he was eventually shot on the tarmac, the ribbon and the song became a rallying symbol of protest against the repression of Marcos’ martial rule until its demise during the first People Power Revolution in 1986.

The murder of Ninoy on the tarmac ignited the yellow revolution. Yellow was the color of EDSA. People wore yellow T-shirts, headbands, or caps. Yellow confetti showered from tall Makati buildings during the rallies leading to the 1986 snap elections. The Reformed Armed Forces Movement (RAM) of Ramos and Enrile wore them as arm bands as distinguished from the Marcos loyalist forces who wore white armbands.

We wore yellow but we did not call ourselves “dilawan”. We just wanted to protest against the dictatorship. We just wanted Marcos out. When we shouted “Tama na. Sobra na. Palitan na”, we shouted while wearing yellow. Yellow was a color of resistance. It was not only about Cory or Ninoy but about what their lives symbolized — martyrdom, hope, and love of country. It was also more against Marcos, against Martial Law, against the repression — and all that he represented.

Pass forward. It was Duterte and his minions who started using the word “dilawan”. As they positioned themselves to take over the national political power from the south, their program started with vilifying the yellow, Noynoy Aquino, then president, and all that he represented. Dilawan was used with words like “Noynoying”, “corrupt oligarchs”, “elite liberals”, and “Manila imperialism”, as distinguished from the rule of the ordinary people which identified itself as coming from the poor and the grassroots. In this well-financed marketing campaign, Duterte was portrayed as a poor man, eating in small carinderia with bare hands and at the same time erasing the many poor people who have been killed in his violent War on Drugs.

From a symbol of protest and liberation, “diliwan” was turned into a symbol of disgrace and humiliation, of misrule and incompetence. This move was reminiscent of how the Nazis used the yellow Star of David — originally a holy symbol for the Jews — as a badge they should wear to distinguish them from the Germanic pure race during the holocaust.

Around the same time (2015 or earlier), Marcos Jr and his family also wanted a political comeback. They wanted to redeem their name by joining the dilawan vilification bandwagon. With Cambridge Analytica and the money poured into the online trolls, the “dilawan” and EDSA were portrayed as the “original sin” of what was then labeled as a glorious paradise of the Marcos Presidency — simultaneously erasing the killings, corruption, and repression of this darkest moment of our history. The Aquinos were portrayed as corrupt and Marcos Sr was the “best President” we ever had. This long-running narrative is fully amplified in social media in a most expensive effort to rewrite history.

The sad truth is, it continues to this present day.

The combination of these political forces and their revisionist program came to its peak in the UNITEAM campaign. They are red and green. This time, Yellow has totally retired from the scene. Even the opposition branded itself as “pink”. And if ever there was a taint of yellow among the political aspirants, they were mocked as “pinklawan”.

In reality, colors do not exist in themselves. Color is a social phenomenon. People make colors and assign them their meanings. They also change it according to their fluctuating social sensibilities and shifting political intents and purposes.

Upon his arrival in Arles and Saint Remy in the south of France, the famous Vincent van Gogh wrote to his brother Theo: “The sun dazzles me and goes to my head, a sun, a light that I can only call yellow, sulphur yellow, lemon yellow, golden yellow. How lovely yellow is!”

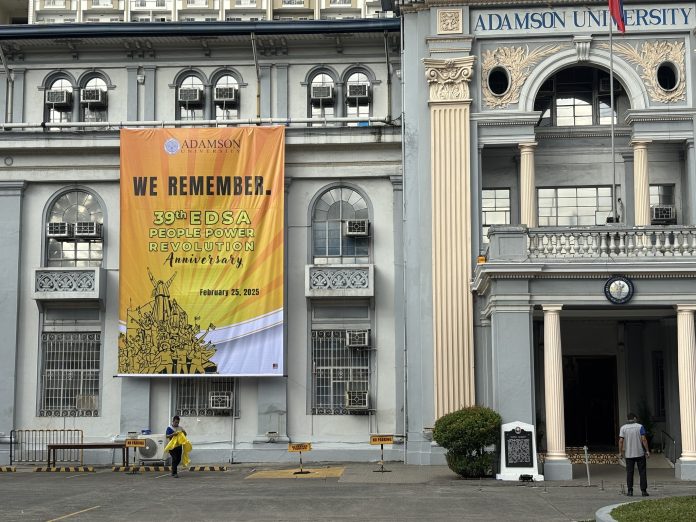

Father Daniel Franklin Pilario, C.M., is the President of Adamson University in Manila. He is a theologian, professor, and pastor of an urban poor community on the outskirts of the Philippine capital. He is also Vincentian Chair for Social Justice at St. John’s University in New York.