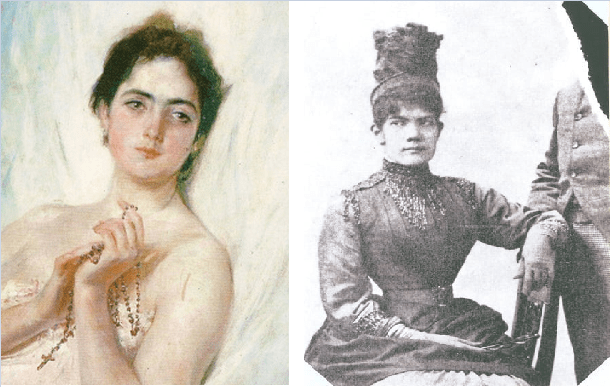

The “Portrait of a Lady” or “Mi Novia” is Juan Luna’s famous painting, often mistaken as that of his wife, Paz Pardo de Tavera, who became a victim of a crime of passion.

The painting depicted a woman in bed, clutching a rosary, with a prayer book and a nightstand to her left.

Although Luna was fond of his wife, he was unfortunately also prone to fits of violent jealousy. Luna was known as a man of violent temper as Paz was subjected to physical abuse that increased in frequency and viciousness while they were in Paris.

He felt that he was being pushed out of the marriage through a conspiracy involving his in-laws, the Pardo de Taveras, as Paz was seeking separation and custody of their child. He also suspected his wife of infidelity and was engaged in an affair with a certain Maurice Dussaq. He became suspicious and paranoid of everything around him.

Luna’s violence towards his wife would intensify until that tragic day of September 22, 1892, when he went into a jealous rage and shot his wife and mother-in-law, Doña Juliana Gorricho Pardo de Tavera in the head. Juliana died on the spot while Paz followed eleven days later.

Luna was acquitted on February 8, 1893, as the charges were dismissed on the grounds of temporary insanity caused by passion. There was an unwritten law in France at that time that gave leniency to the so-called “honor killings” wherein husbands are allowed to punish or kill their wives suspected of adultery.

If Luna were tried at present in the Philippines, the outcome could be different.

Passion and obfuscation can be used only as mitigating circumstances under the Revised Penal Code (RPC) or those which if present in the commission of the crime do not entirely free the actor from criminal liability but serve only to reduce the penalty.

RPC Article 13 mandates that to be able to successfully plead the mitigating circumstance of passion and obfuscation, the accused must be able to prove the following elements (1) that there be an act, both unlawful and sufficient to produce such condition of mind; and (2) that said act which produced the obfuscation was not far removed from the commission of the crime by a considerable length of time, during which the perpetrator might recover his normal equanimity. (Poso vs People G.R. No. 210810, December 07, 2016).

There is passional obfuscation when the crime was committed due to an uncontrollable burst of passion provoked by prior unjust or improper acts, or due to a legitimate stimulus so powerful as to overcome reason. The obfuscation must originate from lawful feelings. (People v. Lobino, 375 Phil. 1065). There must be causes naturally tending to produce such powerful excitement as to deprive the accused of reason and self-control (People vs Leonor, G.R. No. 125053 March 25, 1999).

Acts done in the spirit of lawlessness or revenge (Napones vs People, G.R. No. 193085, November 29, 2017) or with treachery or evident pre-meditation (People vs. Pagal, G.R. No. L-32040, Oct. 25, 1977) cannot be considered acts done with passion or obfuscation.

There is no uniform rule on what constitutes “a considerable length of time.”

The Court ruled in the negative due to the lapse of thirty minutes ( People v. Rabanillo, 367 Phil. 114), more than 24 hours (US v. Sarikala 37 Phil. 486), three days (People v. Caber, Sr., 399 Phil. 743), four days (People v. Constantino (G.R. No. L-23558. August 10, 1967) seven to ten days (People vs Layson. G.R. No. L-25177. October 31, 1969.), reckoned from the commission of the act which produced the passion or obfuscation up to the time of the commission of the felony.

In People vs Oloverio ( G.R. No. 211159, March 18, 2015), Justice Marvic Leonen explained that the provocation and the commission of the crime should not be so far apart that a reasonable length of time has passed during which the accused would have calmed down and be able to reflect on the consequences of his or her actions. What is important is that the accused has not yet “recovered his normal equanimity” when he committed the crime.

Leonen added that passion and obfuscation as a mitigating circumstance need not be felt only in the seconds before the commission of the crime. It may build up and strengthen over time until it can no longer be repressed and will ultimately motivate the commission of the crime.

In People vs. Brusola (G.R. No. 210615, July 26, 2017 ), Leonen did not consider the murder as a crime of passion. “There is never any justification for a husband to hit his wife with a maso (mallet). The promise of forever is not an authority for the other to own one’s spouse. If anything, it is an obligation to love and cherish despite his or her imperfections. To be driven to anger, rage, or murder due to jealousy is not a manifestation of this sacred understanding. One who professes love should act better than this. The accused was never entitled to hurt, maim, or kill his spouse, no matter the reasons. He committed a crime. He must suffer its consequences.”

I am still doing my research that Gorricho perhaps is a variation of my surname Gorecho. Juliana gave the lamp/ stove to Jose Rizal where the paper of “Mi Ultimo Adios” was found.

Atty. Dennis R. Gorecho heads the seafarers’ division of the Sapalo Velez Bundang Bulilan law offices. For comments, e-mail [email protected], or call 09175025808 or 09088665786