My grandson turned 20 in March this year. In November, he lost his father. In August two years ago, he lost his mother.

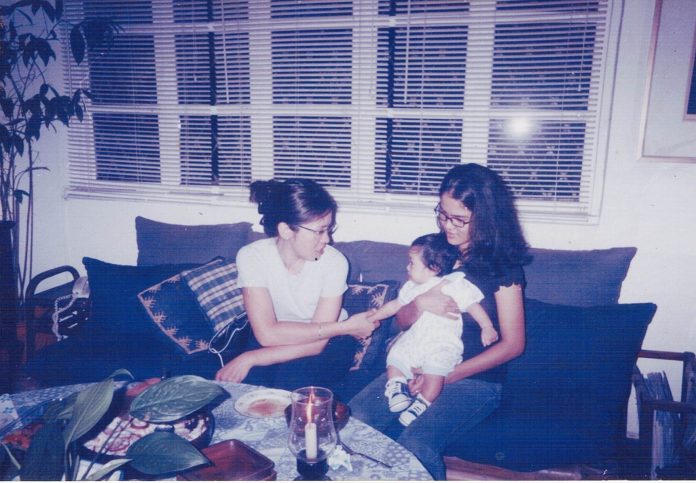

He was named after another activist-poet who died in the South. I took full custody of him since his grade school days.

One way or the other, he changed his grandfather’s routine and the way I look at life. Without household help during his grade school years, I had to do everything – waking up at 4 a.m. to cook breakfast in time for his 6 a.m. class; washing and ironing his school uniforms; attending PTA meetings; and horror of horrors, being present at his first communion that petrified me because the priest sounded like Father Damaso during the homily.

My grandson noticed how I reacted. By now he knows why I don’t go to church even if we have lived near a historic house of worship for many years.

I gave my grandson his first bike. I also treated him to his first movie, his first play, and his first ballet — and he must have realized then that I am closer to the temple of the arts than to a house of worship.

As he grew older, he discovered that his godmother was a famous filmmaker (now National Artist for Film) and his godfather sang jazz, and that my best friend, a pianist, would call at four in the morning.

He’d often wonder why I’d be guffawing on the phone at that unholy hour. Because my pianist-friend would tease me about becoming grandfather of the year, and that I needed just a few more points to be considered for canonization.

It was on my grandson’s 18th year that he lost his mother. I remember how that week looked like. It is easy to say you are prepared to see the worst happening to your daughter because of her life as an activist.

But when you see her picture, cold and lifeless on a mountain trail, you know you need more courage to accept what has happened to her.

I was looking at my grandson that morning while still asleep. My predicament was how to break the news to him. I knew I couldn’t do it.

The next day, my daughter’s violent death was all over Facebook and the newspapers and television news footage. It is the first death in the family. She was the second of my three daughters.

And so her death was all over Facebook. I went into denial, even as I reminded myself it would be better to accept what had happened.

I asked a family friend to come to break the news to my grandson. I didn’t think I could handle it without turning the moment into a scene from a teleserye. The family friend arrived, condoled.

Then I asked him to take on the sad task of breaking the news to my grandson. He did it gently, from what I could figure out.

Minutes later, I saw my very composed grandson. No breaking down. No tears. I even saw him break into a wan smile as if to tell me, “This is not a big deal. I can handle this.”

The sad news transmitted, I let out a sigh of relief. My grandson is made of sterner stuff, and he showed it. Then he told me he knew something was wrong just by reading my face that early morning, while I was trying to confirm the news.

I told myself we could move on and do what had to be done. We had to fly to Bacolod to claim the body. We had to subject ourselves to swab tests to be able to board the plane. We had to apply for Silay and Bacolod passes so we could move around.

That was my first swab test. What if I tested positive? Did this mean only my grandson could fly to Bacolod while I had to face isolation?

The swab test results didn’t come on time by email for us to be able to board the Monday 8 a.m. flight. No way could you board the plane without the results of your swab test, the lady at the check-in counter told us.

We had to rebook our tickets for an afternoon flight. The swab test results finally arrived after the plane had left. My grandson and I tested negative!

We were able to rebook an early afternoon direct flight to Silay-Bacolod airport. Meanwhile, I had to brace myself for what I would see when I claimed my daughter’s body.

I have never been inside a funeral morgue. I have never been inside a dingy room full of dead bodies. Before the plane landed, I had to let go of my quiet sobbing. After all, this was not my idea of my last reunion with my daughter.

First order of the day upon arrival was a briefing with our lawyer, who happens to be a city councilor. I needed to present papers to be able to claim my daughter’s body: birth certificate, marriage certificate, my grandson’s valid ID and birth certificate, and my ID and birth certificate.

Next was the moment of truth. The funeral parlor aide guided us to a room full of dead bodies all covered in white cloth. I looked at my grandson. I wondered how he would react upon seeing his dead mother for the first time.

When I saw my daughter’s lifeless body on that steel stretcher, I let out a long, painful howl of grief. I embraced her and kissed her forehead like the last time we saw each other.

My grandson saw how helpless I was at that moment. Then I felt my grandson’s hands massaging my shoulder as I cried endlessly. My grandson’s inner strength was unbelievable.

No tears for him. No breakdown like I had. I never thought lightning would strike twice in a couple of years. As I write this, it’s been eight months since another family tragedy struck.

As the country observed Andres Bonifacio Day last November 30, I got curious about a news item on another reported encounter between military and rebel groups in Barangay Kamansi, Kabankalan, Negros Occidental.

I immediately sounded off my media friends in Bacolod. In another Facebook post on the same day, we learned that my son-in-law, Ericson Acosta, and his companion were arrested on the same day at about 2 in the morning.

I immediately asked my grandson to sound off his maternal grandmother, 90-year-old Liwayway Acosta. I took it lightly and hoped, if worse came to worst, that my grandson and I would still get to visit Ericson in a detention hall.

But before noon of the same day, November 30, a friend confirmed another death in the family. He wasn’t detained after arrest. A witness claimed that he was made to walk around the house where he was arrested, then was allegedly struck down.

Meanwhile, the local media ran a military account of an alleged “encounter” with “rebels.”

After Ericson’s death was confirmed, I stared at my computer and let out a howl of grief.

I was only thinking of my grandson who has been orphaned twice in just two years. He was with his University of the Philippines (UP) friends observing Bonifacio Day in Mendiola, when he got wind of the news ahead of me and his maternal grandma.

Somebody described how he saw my grandson pause, apparently stunned by the news, and quietly walk to a street corner and cry. I never saw him cry when his mother died.

This was a repeat scenario: on the day we heard the news, we had to book a flight to Bacolod, and to work on assorted permits before we could claim the body in a Kabankalan funeral parlor.

It is a two-hour ride to Kabankalan from Bacolod in the early morning. First, we had to get an incident report from Barangay Camansi. The barangay head didn’t want to sign the incident report, but with gentle prodding from our lawyers, he did sign, but not before he made us aware that he was king of his turf.

My grandson knew the routine would be similar to when he claimed his mother’s body a year ago in a Silay funeral parlor. We needed not just a barangay clearance but also police clearance, health clearance, city hall clearance, and once done, we needed an embalmer’s signature to confirm the existence of the body.

We spent a whole day doing that, running around various offices and getting derailed by the absence of officers who were out attending seminars.

A doctor was available to sign the health clearance only on December 12. We could not wait that long, and it was only December 1 when we arrived. We decided that we would transport the body to Manila and have it cremated later.

The funeral parlor, on the outskirts of Kabankalan, was surrounded by men in uniform the day we went. We learned later that the owner was a traffic enforcer and a Christian pastor on the side.

This was the moment I feared: when my grandson would see his father’s lifeless body in a roomful of dead people.

Three years back, right before Christmas, he had a few days with his parents in Bacolod. Just after my last concert at the Nelly Garden in Iloilo City in 2019, I met my grandson in an inn and gave him a room and breakfast before he headed to Bacolod on a ferry boat.

That was the last time my grandson saw his parents alive.

Past reunions with his father included frequent visits to a Calbayog jail in 2012-2013. When we finally saw the body of Ericson, I couldn’t help looking at my grandson. I have never seen that face so devastated.

When his mother died, he took it all calmly. Or so I thought. Seeing him before his father’s body, I thought I couldn’t bear the sight. I took a quick look at my grandson’s face and saw loneliness of a devastating kind.

I retrieved the clothes of his father from the funeral parlor embalmer, after which we headed back to Bacolod fast to get another permit to bring the body back to Manila.

“You want to see Tatay’s body before we bring him to the airline’s cargo office? We bought him new clothes,” said my grandson. “No,” I said. “I will see him in Manila anyway. Let’s just have a quick dinner.”

We realized we had missed our Friday lunch, busy as we were getting all those required permits. My grandson and his ninang flew ahead to Manila with his father’s body to arrange for cremation. We followed later on the afternoon flight.

Back in Manila, we prepared for a Requiem Mass before cremation. My grandson received a metal rose from a mother whose daughter had been incarcerated also for years. Then grandson and I watched Ericson’s body as it was brought to the hot furnace.

I realized my grandson and I had been witness to the cremations of his parents the past two years. In the final tribute to his father at the Gumersindo Garcia Hall of UP Diliman, my grandson had come to terms with another death in the family.

On a lighter note, he spoke candidly of his father as a musician: “I am my father’s worst critic. I am always critical of everything he does. I notice he plays the guitar with just one chord. So I called him “The One-Chord Wonder.” There was laughter from the audience.

Then his final remarks, which went viral on the internet and reached more than five million netizens: “I have nothing against my parents for spending more time with the poor and the oppressed than with me. I believed in what they fought for. There is no rancor in my heart that my parents have other families—the masses. That was made clear to me by Tatay and Nanay.

When they were heartlessly killed, the more I believed in their cause.”

On the day Ericson joined my daughter Kerima in the grave, I could only react with another poem.

We are done

With grieving

And wiping away

Persistent grief

Like my grandson

Who let it all fall

Where it should

On a street corner

Where his parents used to tread

Along the hollowed street of Mendiola

What were those tears for?

He expected to reunite

With dear father

In a detention cell

And perhaps make music

Together

For the last time

The next thing he knew

His father was arrested

In the hinterlands of Kabankalan

Then made to do a few turns

With his companion

Only to meet their imminent death

In a sudden rain of bullets

And bolos tearing away

At their skin

Months back

I always requested

Massenet’s Meditation

To remember

My late daughter

Now it is time

For that soulful music

To remember his father

I always ask my grandson

To sit with me in rehearsals

While Massenet’s Meditation

Floats eerily

In the auditorium

Surely

Music has a way with grief

Perhaps it is a good way

To confront death

Perhaps the gentle way?

Now tell me

How should music metamorphose

Into balm

For our weary spirit?

Perhaps music

Can guide us

Into the periphery of acceptance

Even if the labyrinth

Is oozing

With excruciating pain

I did carry that urn

With his mother a year ago

Now I am torn with grief

Seeing him

Carrying his father’s ashes.

Is it

Time to move on

And fly on the wings

Of song

And remembrance?

By and large, 20 years with a grandson allows you to review what living and coping are all about. You learn to cope when he is sick, and you call his pediatrician in the dead of night asking what to do with an overly high fever.

When he comes home with medals and citations, you realize that your little sacrifices have paid off, and you are glad you are still alive to enjoy life with a child who has learned to live without his parents. In time, he realizes that you only earn so much and that your circle of friends is so tight.

If I can help it, I will spare my grandson my private woes. But one I could not hide from him was when his godmother (the filmmaker) died and I let out a howl of grief when I heard her death announced on TV.

He probably understood why I skipped the wake. I asked him how she looked in her coffin; he said she looked beautiful and at peace.

In your grandson’s 20th year, you know you only have a few more good years to spare. One of your eyes has started to dim, requiring visits to an ophthalmologist.

Your hypertension has graduated to another critical stage, and you are constantly advised to see a cardiologist to make sure you will survive another week of deadlines. It won’t be long when you’d need a wheelchair to watch shows at the Metropolitan Theater and before boarding another domestic flight.

The signs of autumn are all there: You keep hitting the glass door of a Makati museum before a concert, you keep missing a step while looking for your seat at an event. You could have made a spectacle of yourself when you nearly rolled down the aisle before the curtains rose.

Like it or not, 20 years of “single grandparenthood” is a badge of honor, and you are amply rewarded when your grandson comes home announcing that he won this and that Metro Manila competition.

He won hands down in a nationwide quiz on Chinese history. I look at his picture at the Great Wall of China (part of his prize) with love and pride. I don’t expect to visit Beijing in my lifetime, and I am glad my grandson did.

I am glad my grandson has a band now getting its fair share of recognition in the rock circle.

Tuesday afternoon, I saw him off for his first out of town engagement. Without the band, I don’t know how he will cope.

But life must go on. He is now a third year BS Math student in UP Diliman.

On Friday, a forensic expert will tell me what really happened to my son-in-law based on her examination. You have accepted what happened to your grandson’s father. But hearing the details of what caused his death is another story. You will discover more lies peddled by his murderers. And you wonder how much more can your grandson take.

Pablo A. Tariman, 73, is the author of the book of poetry, Love, Life and Loss – Poems During the Pandemic, published by Music News and Features. Two of his poems are included in the anthology The Best Asian Poetry 2021, published by Kitaab Publishing in Singapore. His poem, “The Woman on a Motorcycle” appears in the anthology, 100 Pink Poems para kay Leni. Tariman was born in Baras, Catanduanes, and has six grandchildren.

EDITOR’S NOTE: Earlier versions of this article first came out in TheDiarist.ph and Philippines Graphic.