Amid majestic mountains and emerald streams, Younis Iqbal spent days and nights in a makeshift shelter. He has been away from home for the past 15 days already to work at the Amarnath Temple, a Hindu shrine in the Anantnag district of Jammu and Kashmir.

The cave is situated at an altitude of 3,888 meters, about 168 kilometers from the city of Anantnag, the district headquarter, 141 kilometers from Srinagar, the summer capital of Jammu and Kashmir.

For years, Younis has been working as a helper of pilgrims at Baltal, a camping ground on the way to the holy shrine that is known for its scenic beauty, meadows, pony rides, and even helicopter services.

The annual pilgrimage, which runs from mid-July to mid-August, has become a source of income for Younis who, like thousands of young locals, works as porter, horseman, and guide.

They would help pilgrims trek the treacherous mountains to have a glimpse of a stalagmite that forms every year on a wall of a remote cave.

The nine-foot-tall ice sheet, shaped like a phallus, is considered to be a symbol of Lord Shiva, one of Hinduism’s three most revered gods. The Amarnath pilgrimage symbolises harmony between Hindus and Muslims in the region.

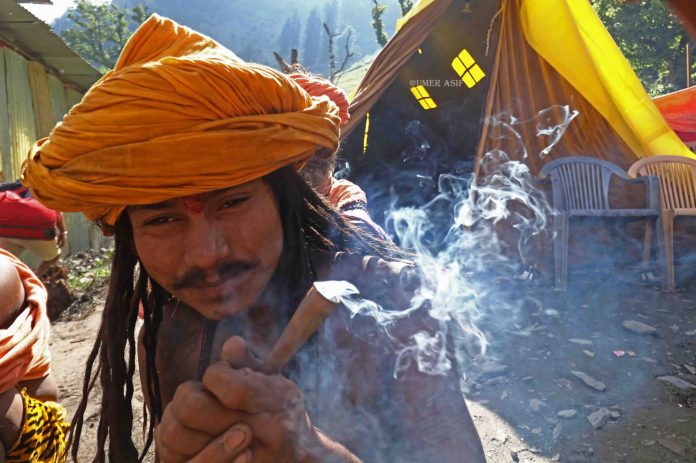

Shouting ”Hail, Hail Shiva!” and ringing ceremonial bells, devotees are taken to the cave by Muslim horsemen and porters through rocky pathways that snake around the mountains where oxygen levels dip and weather changes unexpectedly.

Ishtiyaq Ahmed, a horseman, said he earns his livelihood from the pilgrimage even as he claimed that he also feels “a sense of satisfaction” in serving the devotees.

“There are so many ways to earn money, but here I serve the devotees and help them in attaining solace. It gives you a great sense of satisfaction,” he said.

Local legend claims that the pilgrimage started when a shepherd discovered the peculiar ice formation in the cave in the late 1700s. A Hindu priest who visited the site declared the calve the mythical home of Lord Shiva.

Until the Indian state was formed in 1947, pilgrims were only a few thousand, mostly ascetics and Hindus from nearby areas.

The number of people rose in the mid-1980s but dipped later when armed conflict hit the region. The number of pilgrims steadily increased to 600,000 since 2010 when the pilgrimage, traditionally held for two to three weeks, was extended to up to eight weeks.