In the eight years that Basudev Pokharel has worked as a forest guard, he has rarely seen a fire as huge as the one that raged through his village in western Nepal in March.

Hundreds of such fires have been spreading across the country since November, in the worst wildfire season Nepal has seen in a decade.

The night the blaze reached Pokharel’s village of Sungure, in Dang district, a neighbor woke him to warn him.

“We tried to control the fire, but it spread so rapidly that we were helpless,” the 55-year-old recalled.

“The fire came very close to my house and burned all the hay that I had piled up to feed the animals. Luckily, I could save my house.”

The government sent a fire control expert to direct the villagers as they tackled the blaze, and by the next day it was out — but only after destroying more than 80 hectares (198 acres) of forest.

“That night, I couldn’t sleep the whole night,” Pokharel said, as he worried that another fire would make its way to Sungure — one the villagers could not fight.

As large swathes of Nepal and some northern parts of neighboring India continue to burn, the smoke and ash have caused air pollution levels to spike, with experts warning increasingly frequent droughts linked to climate change could make massive wildfires more common.

Pokharel said the fire reached his village through the surrounding forest, where a lack of significant rainfall for the past six months has left leaves tinder dry.

Villagers say the fire has been a disaster for the 460 households who live near the forest and rely on it for food and fuel, in a country that prides itself on its community-managed forests.

“Many people here depend on firewood as their cooking fuel and much of it has been destroyed by the forest fire,” said Bimal Kumar Bhusal, one of the villagers.

“We are also going to face a shortage of grass (for animals) as it has all been burned down,” he added.

‘Hazardous’ air pollution

According to Bijay Raj Subedi, a forest officer in Dang, wildfires in Nepal are most often caused by humans, either internationally or by accident, such as when a cigarette is carelessly discarded.

Villagers regularly set fire to trees to create charcoal, to scare animals out of hiding so they can hunt them, or to clear areas in the hope of encouraging the growth of mushrooms or new flushes of grass.

But an unusually dry winter this year has meant smaller fires can more easily spread out of control, Subedi noted.

“There had been almost no forest fire incidents in Dang last year, as we had good rainfall,” he said, adding that this year there have been more than 20 major forest fires in the district.

Figures from the Department of Hydrology and Meteorology show there has been about 15 mm of rain in Nepal this winter, 75 percent less than average.

According to Nepal’s disaster risk reduction agency, more than 2,700 fire incidents were recorded between mid-November 2020 and the last week of March, a time period that covers most of the dry season.

This is the worst fire season in terms of number of fires since the country started keeping records in 2012, and more than double the previous high of 989 wildfires in the 2015-2016 dry season.

The air quality index (AQI) has recorded pollution levels in Dang above 100 most days since last month. An AQI level below 50 is considered good.

Last week, levels in the capital Kathmandu were above 470, which is categorised as hazardous.

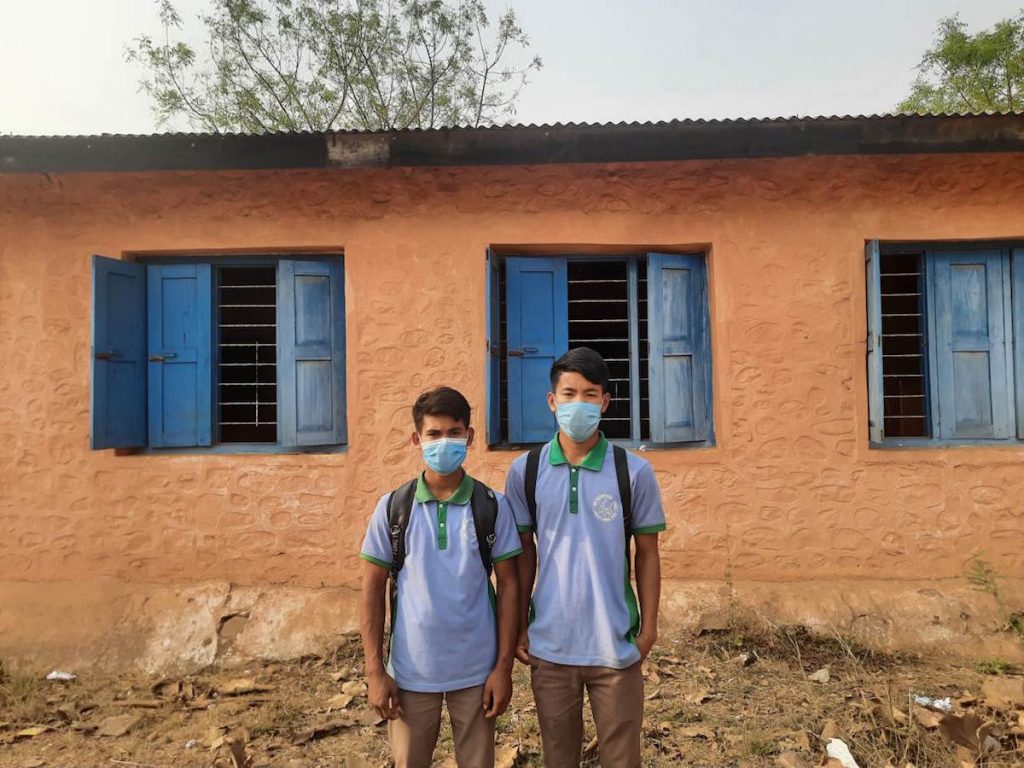

Schools around Nepal were closed for four days at the end of March, as students complained of irritation in their eyes and throats from the smoke.

Although schools are open now, “students are (still) missing class due to different health issues,” said Bhakta Bahadur Marsangi Magar, vice principal of Saraswati Higher Secondary School in Pyuthan, a district next to Dang.

“Those who are attending are not concentrating much as almost everyone is having issues such as burning eyes,” Magar said.

But there was no point to closing schools again “as we are not sure when the pollution level will come down,” he said.

He said his school is encouraging students to wear masks in the classroom.

Out of control

Naya Sharma Poudel, a coordinator for Forest Action Nepal, a nonprofit based in Lalitpur, said while forest fires are not the sole cause of rising air pollution in Nepal, “they are definitely one of the major causes.”

Poudel pointed to lack of manpower as a reason Nepal’s forests are so vulnerable to wildfire.

Prakash Lamsal, a spokesman at the Ministry of Forests and Environment, said villagers are trained to work with each district’s forestry officers to contain and extinguish fires in their areas, using fire lines along with equipment provided by the district government.

“However, the spread of the fires this year was so rapid that most of the forest fires in the country are out of our control,” he added.

Poudel said the migration of job-seeking young adults from villages to towns and cities has left rural communities with fewer people able to fight fires.

“Villagers have to rely solely on government bodies to control fires,” he said. “By the time help arrives in these far-flung forest areas, the damage is already done.”

Poudel said forest floors should be regularly cleared of dried leaves and branches to slow the spread of fires, and the government should build ponds dotted around forests to ensure water is more easily available whenever a fire breaks out.

In Pyuthan, vice principal Magar just wants the air to clear so he and his teachers can safely help students prepare for upcoming exams and catch up on lessons delayed due to the country’s COVID-19 lockdown.

“We are so far away from the city, very close to the forest. I never thought that pollution would be an issue for us,” he lamented.

Reporting by Aadesh Subedi for the Thomson Reuters Foundation, the charitable arm of Thomson Reuters, that covers the lives of people around the world who struggle to live freely or fairly.