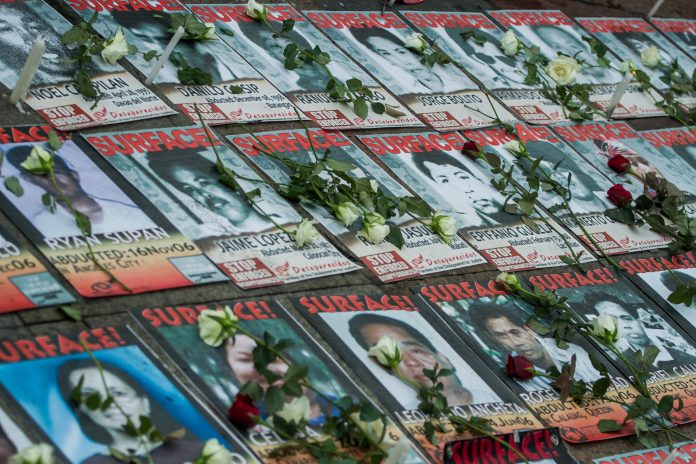

Without tombs to visit and hampered by a typhoon to hold gatherings, families of victims of enforced disappearances, or “desaparecidos,” posted photos and videos online of their missing loved ones.

On the eve of All Souls’ Day, kins of missing activists posted on various social media platforms to call for justice.

Every year, on November 2, families of “desaparecidos” gather in front of a Catholic church in Manila to remember missing loved ones.

This year’s event, however, was postponed due to a typhoon that hit the country on November 1 and the coronavirus pandemic.

Erlinda Cadapan, chairperson of Desaparecidos-Families of the Disappeared for Justice, said “these conditions should not and could not stop us from reiterating our call for justice.”

“In times that we cannot gather on the streets, the internet is a venue that we must maximize to spread public awareness about the victims of state-sanctioned enforced disappearance,” she said.

Cadapan told LiCAS.news that the public must be made aware that “the desaparecidos have names, stories, faces, and families who were denied to grieve.”

“Families of missing activists are deprived to grieve for their loved ones because the perpetrators of abductions refuse to surface their bodies or reveal what really happened to them,” she said.

Cadapan is the mother of student activist Sherlyn Capadan who went missing in 2006 with another University of the Philippines student, Karen Empeno.

In 2018, Army general Jovito Palparan was sentenced to life imprisonment after being convicted of kidnapping and serious illegal detention over the disappearance of the two students.

To date, at least 1,200 people have become victims of enforced disappearances in the country since the years of martial law in the 1970s.

Desaparecidos-Families of the Disappeared for Justice has documented 13 cases of enforced disappearances since July 2016 under the administration of President Rodrigo Duterte.

The most recent cases include the alleged abduction of community organizer Joey Torres, indigenous people leaders David Mogul and Maki Bail, and human rights worker Honey Mae Suazo.

Filmmaker JL Burgos, brother of missing peasant activist Jonas Burgos, expressed warned of “more cases of enforced disappearances” following recent threats against activists.

“Activists and human rights defenders are being labeled and tagged as communist or terrorist, which we know could lead to killings or enforced disappearances,” he said.

The Philippines is the only country in Asia that enacted a law criminalizing the practice of enforced and involuntary disappearances.

In December 2012, the country passed the landmark Anti-Enforced or Involuntary Disappearance Act.

“Despite the existence of a law, activists, farmers, and rights workers are still subjected to involuntary disappearances,” said Father Dionito Cabillas, convener of faith-based rights group Isaiah Ministry.

“The government and all sectors of society must act against this evil act. No person, regardless of political belief, affiliation, or ideology must be subjected to enforced disappearance,” he said.