No fancy footwork. No laurels up for grabs. No special effects.

Just plain old fearless journalistic storytelling.

As storm Quinta (#Molave) made landfall in Albay and battered the Bicol Region and Catanduanes on the evening of Oct. 26, 2020, I was whisked away by the howl of strong winds back to the wee hours of Nov. 8, 2013.

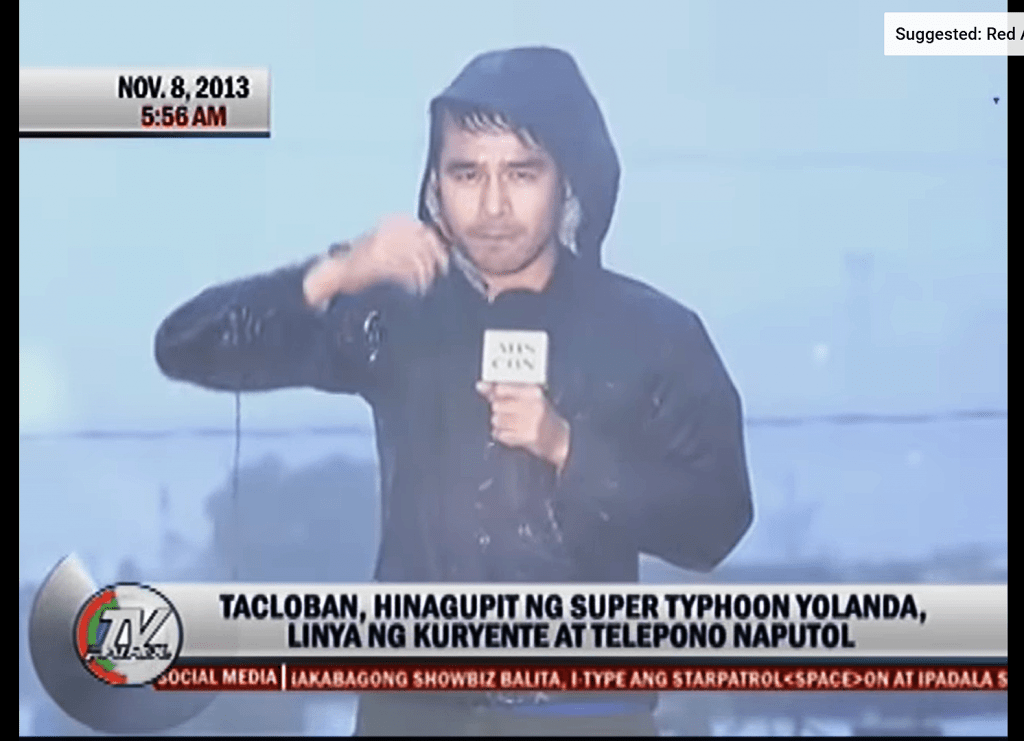

A quarter past five in the morning of that day, ABS-CBN correspondent Atom Araullo, in a near-to-tattered raincoat, defied Yolanda’s 315-kilometer-per-hour winds—not to mention rocketing galvanized iron sheets torn from rooftops, crumbling business signboards, broken glass flung from windows, and every other flying debris imaginable—and made every effort to capture the storm in a news bottle.

The aftermath left Tacloban and all provinces within the path of the storm profoundly scarred for a significant amount of time. The Category V super typhoon (also known as Haiyan), with an estimated storm surge of four meters, cut a swathe of devastation all across 591 municipalities and 57 cities, with 1.19 million damaged homes and more than 10,000 deaths. Roughly 12.2 million people were displaced.

Barely a month following the devastation, the National Economic and Development Authority’s (NEDA’s) report on Dec. 2013 said that Yolanda had left the country reeling from an economic fallout.

“The total damage and loss from typhoon Yolanda has [sic] been initially estimated at PhP571.1 billion (equivalent to US$12.9 billion12). About PhP424.3 billion of the total damage and loss represents the value of destroyed physical assets, while the remaining PhP146.5 billion represents reductions in production, sales, and income to date and in the near term.”

Thanks to ABS-CBN’s storm chasers, the farthest reaches of the country, nay, the world, received a blow-by-blow account of Yolanda’s rage and how a people of little resources displayed a level of resilience only few others can.

The recent closure of ABS-CBN—both its Manila and regional networks—by a Congress too busy with Pres. Duterte’s navel has left the country well-nigh blind. As Storm Quinta swiped the Bikol region and Catanduanes, many felt a stark lack in news coverage.

Journalists themselves saw how ABS-CBN’s reach informed far-flung provinces of incoming storms. This gave local government units as well as the populace time to prepare should the call to evacuate was given out.

National Union of Journalists of the Philippines (NUJP) director Nonoy Espina noticed how the closure of the largest network in the country may have affected the dissemination of news to outlying areas.

In a social media post, Espina said, referring to those who ordered the closure of the network, “There are places that might not have known Quinta was coming because only ABS-CBN could reach them. Are you happy now?”

Journalist Jacque Manabat also said, “Sa mga ganitong panahon, nakaka-miss ang ABS-CBN Regional Network Group” (In times like these, we miss the ABS-CBN Regional Network Group).

Jamela Aisha Alindogan, broadcast journalist for Al Jazeera, also weighed in. “In times of natural disasters, the lack of news can be felt in far-flung provinces. ABS-CBN has the widest reach, news is updated and can reach the farthest corners of the country. People had been deprived.”

On July 10, 2020, instead of finding solutions to an ongoing pandemic, the House Committee refused ABS-CBN its franchise renewal, forcing the network to close shop and lay off 11,000 of its workers.

Sometime middle of August, 53 regional television and radio stations transmitting in six Philippine languages saw the airing of their final broadcast upon orders from the Duterte government, denying Filipinos access not only to their favorite programs but the news.

The Foreign Correspondents Association of the Philippines (FOCAP) described the shutdown of ABS-CBN’s regional stations as an “avoidable national tragedy, inflicted by the very people who should protect Filipinos from all adversity.”

In a country where an average of 20 storms and hurricanes crisscross the archipelago each year, isolated communities will now have no way of knowing when and where these disasters will strike.

While the internet offers ABS-CBN’s remaining news bureau the chance to continue its work of informing the public, surveys on local internet speed, to say little of access to it, leaves much to be desired.

OpenSignal’s 2020 report, “The State of Mobile Network Experience 2020: One Year Into The 5G Era,” released in May, the Philippines does not even appear in its Top 10 list of improved 5G experience. The list is topped by South Korea at 59.0 Mbps followed by Japan (52.4 Mbps) and Norway (47.5 Mbps).

As for download speed experience, the Philippines (8.5Mbps) lands in 83rd place of 100 countries, which, according to the study, is already a 21.5% improvement from 2019.

As for video experience, the country lags at 91st place of 100 countries, roughly seven notches above poor.

Over all, the report indicates that the Philippines has an average download speed of 8.5 Mbps, upload of 2.7Mbps, 81.5% use of 4G technology, 35.4% video experience, and 63.5% voice app experience.

Crunching numbers on paper is quite different from what is happening on the ground. As the world moves indefinitely into cyberspace due to the pandemic, covering stories from far-flung provinces were anything but reassuring.

If only to get a whiff of internet signal, many in the provinces scale mountains, climb coconut trees, stay hours on rooftops, courting very real risks and dangers in the search for an internet signal.

I recall a story published by Anna Bueno and Jessamine Pacis of CNN Philippines a couple of months after the Luzon-wide lockdown.

“In the same Twitter account, there is a photo of Berdida climbing a coconut tree, in the hopes of securing a strong internet signal […] Just a few weeks after on May 16, Kriselyn Villance, criminology student at Capiz State University in Dumarao, Roxas, died due to a motorcycle accident after searching for an internet connection in nearby barangays. She was 20 years old.”

Based on a report by The Asian Post, only the National Capital Region (NCR) enjoy significantly faster speeds compared to North Central Luzon, South Luzon, Visayas and Mindanao.

“NCR showed the least speed fluctuation of 12 megabytes per second (Mbps) between fastest and slowest 4G download speeds within a day, while users in North and Central Luzon experienced the greatest range with a difference of 15.7 Mbps between quiet and busy times.” The signal peaks from midnight to 6AM, and fluctuates all throughout the day. It plummets to a low 5.0Mbps sometime 6PM only to rise before midnight.

News, for it to be instrumental in helping people face disasters, must be disseminated in real time. Any lag in the signal could mean a life-and-death struggle for many Filipinos living in far-flung provinces.

I laud the efforts of other news bureaus to cover what had happened in the wake of typhoon Quinta. In fact, ABS-CBN correspondent Dennis Datu’s coverage of Typhoon Quinta made waves over social media. However, Facebook algorithm somehow prevents it from reaching the farthest ends of the archipelago. For this to happen, it has to be shared and reshared.

Apparently, nothing beats on-time live television broadcasts and correspondents on the scene. The shutdown of ABS-CBN is truly a disservice to the Filipino people.

Joel Pablo Salud is an editor, journalist and the author of several books of fiction and political nonfiction. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official editorial position of LiCAS.news.