BARELY 100 days into a new Malaysian government and a familiar cloak is once again descending over the nation as ministers look to stifle free speech and anyone who criticises them.

The recent police grilling of anti-graft activist Cynthia Gabriel over her ministerial corruption allegation the latest in a growing list of attempts to destroy opposition to the government by bullying dissenters into silence.

The Perikatan Nasional (PN) coalition — a convoluted clutch of Malay-centric political parties and allegiances — wrested power from its reformist Pakatan Harapan (PH) adversary in February after the all-Malay Bersatu party inexplicably dropped out of PH and switched sides.

Bersatu then stood shoulder-to-shoulder with the once dominant Umno and Islamist PAS parties.

The kick in the teeth for many reformers was that Umno — the Malay nationalist party, which for decades had ruled with virtual impunity and had been riddled with corruption, culminating in the infamous 1MDB scandal — was back in charge and clearly relishing the opportunity to reassert itself, despite having been resolutely trounced at the ballot box in 2018 and subsequently teetering on the verge of extinction.

As Prime Minister Muhyiddin Yassin announced his cabinet, those now in opposition had a sense of foreboding as a number of familiar faces reappeared.

Despite Muhyiddin’s reassurances that he would run a clean government free of the authoritarian nature of its Umno-led predecessor, his ministerial choices indicated otherwise.

Defence Minister Ismail Sabri Yaakob set the tone by banning all but two state media outlets from his press briefings, with their questions having to be vetted in advance.

Meanwhile, successive Malaysian prime ministers had relied on a combination of Acts of Parliament — the reviled Internal Security Act, later renamed the Security Offences (Special Measures) Act or Sosma, the Sedition Act and the Official Secrets Act — to keep a lid on any misdeeds and the subsequent public outcry.

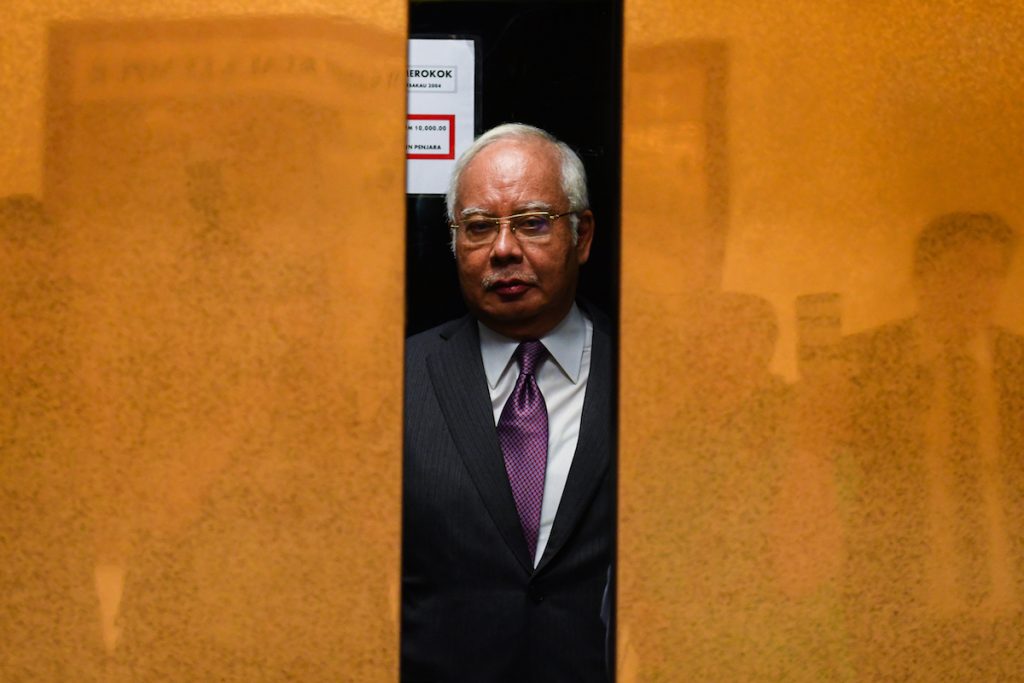

Notably, during the height of the 1MDB scandal, then prime minister Najib Razak had 15 organisers of a mass anti-graft rally in Kuala Lumpur arrested under Sosma, which allows for 28 days detention without trial.

His attempt to crush dissent brought widespread condemnation and — given that his own mentor, Mahathir Mohamad, appeared at the protest — was one small nail in his political coffin. On top of which, he had 1MDB declared an official secret, so opposition MPs could not examine the accounts.

Two years after Najib’s demise as prime minister and parliamentarians on both sides of the house have come to realise that these draconian arrest-and-detention laws need a massive overhaul at the very least, because invoking them will invite a similar fate.

The problem, though, is when you barge into government through the backdoor and carrying a threadbare majority how do you keep people from speaking up when best laid plans go astray?

The answer comes in the form of the Communications and Multimedia Act, which, until recently had been an almost forgotten piece of legislation. More specifically, Section 233(1):

“A person who by means of any network facilities or network service or applications service knowingly makes, creates or solicits; and initiates the transmission of, any comment, request, suggestion or other communication, which is obscene, indecent, false, menacing or offensive in character with intent to annoy, abuse, threaten or harass another person.”

This vague, overarching statement basically gives the government carte blanche to arrest anyone it likes, for the simple reason of offending or even annoying another. The penalty for someone convicted of the crime is one year in prison and a fine of US$11,750.

Naturally for a government intent on imposing its will, what is more annoying or offensive than criticism or healthy democratic debate?

So, CMA 233, as it is known in Malaysia, is now a go-to in the police’s arsenal of legal weaponry against anyone who may feel the need to say: “Hang on a minute…”

Since the day PN took over CMA has been liberally applied, notwithstanding ministerial blunders, the appalling double standards in application of the law, the nepotism and the cronyism.

The police were offended when crime prevention activist R. Sri Sanjeevan called them a rude word on Twitter.

The prime minister was offended by the controversial head of a local taxi drivers’ company, Shamsubahrin Ismail, when he posted a vociferous complaint about trying to operate in the lockdown.

Health Minister Dr Adham Baba was offended by Gabriel’s anti-graft watchdog, the C4 Centre, accusing him of awarding a US$7 million contract to himself.

The government was offended by lawyer Fadiah Nadwa Fikri, who called for protests over the manner in which it came to power.

The government was also offended by former minister Dr Xavier Jayakumar asking why it only convened Parliament on May 18 to hear the royal address and not table other business, thus dodging a no-confidence motion.

Finally, the Immigration Department was offended that South China Morning Post correspondent Tashy Sukumaran’s report on it rounding up thousands of undocumented migrants did not portray the department in the best of lights.

It should be noted that Minister of Communications and Multimedia Saifuddin Abdullah later had the charge against Tashy dropped, but she still faces another similar charge under the penal code for intentional insult or to provoke a breach of the peace.

Meanwhile, the speed at which some of these cases have been fast tracked through the legal system is equally frightening, sending a stark warning to others of what they may face should they decide to have an opinion.

The situation as it stands does not bode well for the coming three years, if PN is to stay the distance until the next general election.

While the dreaded Sosma may well be locked in the cupboard for a more pressing national crisis, CMA 233 looks set to cast a new spectre on a nation just beginning to enjoy the liberty of free speech and healthy political debate.

Gareth Corsi is a freelance journalist based in Malaysia. The views expressed in this article are the opinions of the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial stance of LiCAS.news.