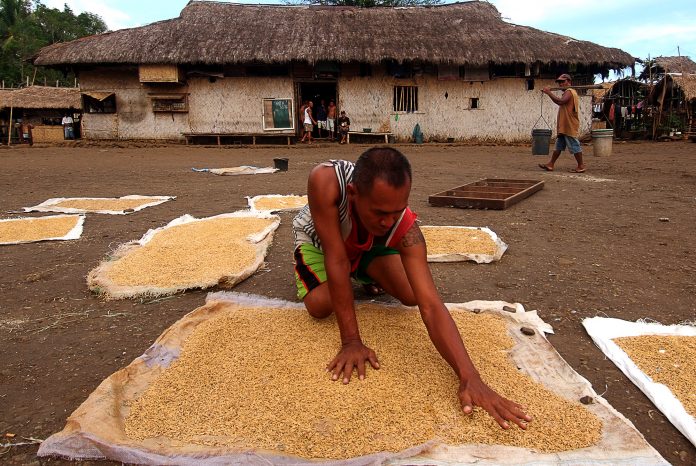

Being a farmer in the Philippines is difficult. These days, it’s doubly hard, said Dhon Daganasol from the town of Carigara in the province of Leyte.

“The weather is getting more unpredictable,” he said. The coronavirus pandemic also took a toll on the poor.

“The pandemic is still with us, greatly affecting small farmers,” said the 49-year old farmer in an interview with LiCAS.news.

While the government claims that it is doing its best to uplift the lives of farmers, Daganasol said he and his neighbors could hardly feel it.

“We have not felt the assistance,” he said. “More often, the support doesn’t suit what we really need. It’s just a waste of government money,” added the farmer.

He cited farm machineries that are not appropriate in the province of Leyte and the vegetable and rice seeds that do not grow in the area.

“It’s a waste of our energy and time,” he said.

“There is support but it lacks proper information dissemination. It seems the government is not really serious in helping,” said Daganasol.

The farmer said he will try to plant ginger in the coming months, during the hot season.

Housing, land rights

In the province of Eastern Samar, 57-year old farmer Lita Bagunas is calling for decent housing and “agricultural assistance.”

Bagunas, who still lives in a “temporary shelter” provided by the Catholic Relief Services seven years after the super typhoon Haiyan disaster, heads the farmers group Movement for Genuine Agrarian Reform in the province.

The group is demanding for government action to “seriously resolve” the housing problems of people affected by the typhoon in 2013.

“[Haiyan] destroyed our lives, livelihood, and houses, and the government is not giving us a sustainable recovery program,” said Bagunas.

She said seven years have passed after the typhoon but people still have to see a decent government resettlement site for them.

“What is painful is the substandard housing they built for us,” she said.

A farmer leader who asked not to be named said people have attended so many dialogues with government agencies to air out their housing issues but their demands remain unheeded.

The pandemic has also restricted them to go out and monitor the construction of the resettlement sites.

Farming no longer fun

“It is already tiresome to farm,” said Ondo Caradilla, a coconut farmer from the village of Tala in San Andres town in the province of Quezon.

Caradilla is one of many small coconut farmers who suffer from the extreme weather events and persistent poverty that have made their lives miserable.

Danny Carranza, a land rights advocate, said the economic situation of coconut farmers took a sharp dive due to unfriendly global market conditions.

“In some areas, coconut farmers are a lot poorer due to constant devastation caused by typhoons, which are manifestations of climate change,” said Carranza.

He said many areas devastated by typhoons are not given the proper assistance for recovery and rehabilitation.

“Isolated communities suffer from lack of attention for being out of government sight and media attention during disasters,” he said.

“This happens because the usual focus of humanitarian response is on areas with the most dramatic images of destruction,” he added.

Carranza said isolated areas unreached by media attention and humanitarian organizations “suffer in silence, and usually take it upon themselves to survive.”

He said the lockdowns caused by the pandemic also took away job opportunities in urban areas and isolated many coconut farmers from traditional markets.

Carranza predicted that in the coming months hunger will intensify, especially among poor farmers who do not know where to turn to for food.

Absence of food policy

Anti-hunger advocates in the country have been calling for the immediate passage of laws to help the government achieve the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals on zero hunger in the Philippines.

“We earnestly request the Duterte administration to certify as urgent the Right to Adequate Food Framework Bill, or the Zero Hunger Bill, now pending in the House and the Senate,” said Aurea Miclat-Teves, president and convener of National Food Coalition.

The bill defines the right to food as a legal right and seeks to end hunger progressively in ten years. It also rationalizes all food-related measures already existing in the country.

Unlike political rights and civil liberties enjoyed by the Filipinos, Miclat-Teves said various laws on rights to food are “non-complementary, inadequately and improperly implemented, incoherent and sometimes in conflict with each other.”

She said “actions must be taken” to implement the government’s National Food Policy that is supposed to address the country’s priority concerns of hunger and poverty.

The coalition also said that there is a need to pass a new agrarian reform law that will respect the rights of indigenous peoples while ensuring the modernization of the country’s agriculture and fisheries sectors.

Citing a report from Philippine Statistics Authority, the coalition of anti-hunger advocates said the estimated poverty rate in the country was 16.6 percent in 2018 and 17.6 million people faced extreme poverty.

“Hunger is one of the critical problems stemming from poverty in the Philippines, with 64 percent of the population suffering from chronic food insecurity,” said the coalition.

A Social Weather Stations survey conducted in September last year also said more than seven million Filipino households have experienced involuntary hunger at least once from June to August this year.

A report from the World Food Program also said that factors such as climate issues and political challenges have contributed to the food insecurity that Filipinos continuously face.

Cabinet Secretary Karlo Nograles, who heads the country’s Inter-Agency Task Force on Zero Hunger, said they already held a series of consultations with stakeholders in government and in the private sector to come up with a “comprehensive and doable set of solutions.”

“We also wanted all stakeholders to actively participate in enforcing the program based on their own inputs,” said the government official.

He said fighting hunger “is a whole nation approach” and everyone should play a critical role.